How we capture research data for agile analysis

Don’t underestimate the value of good notes

User researchers are a bit like wedding photographers. We have to capture what’s happening, what the participant does and what they say, but this is a small part of a researcher’s work. The real value actually comes from the analysis we do afterwards. Much like a photographer spends days processing their pictures to produce the best shots of the day, the time spent analysing data helps researchers produce valid, actionable outcomes.

Conducting research for agile projects requires us to work fast, include the development team and give clients opportunities to get involved. Recently we invited some of the wider team and our clients to note-take during usability testing. We learned that note-taking isn’t that straightforward for those who haven’t done it before, so we wanted to explore ways of better supporting observers.

The benefits for researchers

There’s a lot going on during any research activity. As a facilitator you have to manage the pace and flow of the session, remind participants to think out loud, keep an eye on the time, as well as manage your own behaviour. Having a designated note-taker in the room is therefore vital, as it allows the facilitator to focus on running the session.

Good quality notes are also important, because recording is not always possible: technology fails, people might feel uncomfortable being recorded, or a client might not allow recording.

Most importantly, having someone else observe and take notes allows for faster and more reliable analysis. Someone else’s notes allow researchers to see things from another perspective, therefore providing deeper insights. Academics call this investigator triangulation.

Some tips for note-takers and observers

- Ask the researcher about the structure and purpose of the research so that you don’t end up transcribing the whole thing. Otherwise you’re just getting lots of data, which takes a long time to analyse and gives you a level of detail that’s rarely required.

- Use post-it notes. Write one thing per note so that it is easy to group and move them around later. This also supports visible and collaborative analysis, something we call ‘all on the wall’. In research terms this also known as an affinity diagram.

- Write things that stand out. Watch out for moments of silence, participants asking questions, verbalised emotions and slow reading or talking. This will tell you where participants are having trouble and at what points they need more time to figure things out. But don’t limit your notes to negatives only; it’s valuable to record the good things too. Taking away something that works and supports existing user needs is often worse than failing to improve something that doesn’t work!

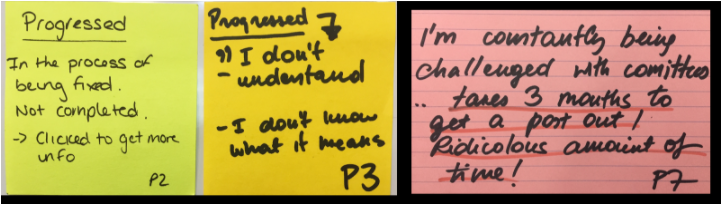

- Capture raw data. This means recording exactly what is being said or done, not what you think it means. This is probably the most important part about taking notes. As a human it is hard to follow the observation, handwrite notes and also consider what they mean at the same time. Analysis should come later when the sessions are discussed with the team, findings are cross checked with other participants, and recordings are referred back to. It’s ok not to be sure about something, so encourage teams to question findings together.

- Write when and where something happened, as well as who said or did it. You should do this without giving away the participant’s identity, unless they have agreed for their identity to be revealed. Researchers commonly use P (for participant) with a number (e.g. P1, P2, P3).

- Have a backup plan. Always try to record the sessions, which is particularly important if you don’t have an observer. Doing so will allow cross-validation when memory fails and are useful for cross-referencing later in the analysis stage, where initial notes may not be comprehensive. You can also use snippets of these to help others empathise with users. At dxw we believe that ‘showing the thing’ works better than words, and video makes that much easier.

- Avoid typing notes. This is distracting for both the facilitator and the participant and can easily introduce bias. To take an example, if you suddenly start typing intensively the participant might feel they have said something of value and might emphasise something they otherwise wouldn’t.

- Make notes of when you feel bias might have seeped in and where something could have been probed more. This will help improve future sessions and explore themes going forward.

- Stay in the shadows so that you don’t accidentally throw off the session or introduce bias. Participants may notice you suddenly scribbling or a change in your body language, or you might be tempted to disclose that someone else said or did something similar. Save all this for the end when there’s an opportunity for observers to ask questions, but don’t betray your own views.

In addition to these tips, there’s lots of blog posts and articles about observing research and analysing findings. Here are a few I particularly like:

- ‘Research analysis in agile’ by GDS– describes a similar way of working to dxw and has a short video.

- ‘Capturing User Research’ by Jim Ross – more in-depth advice for capturing data from qualitative research and suggestions of some cool gadgets to help researchers take handwritten notes.

- Evernote handwriting features – great ideas on how to keep working with post its and handwritten notes, with the ability to save and search digitally.

The dxw research team would love to hear about other ways of working and tools people find useful when researching for agile projects.