Map Camp: The power of maps

The maps at Map Camp are not geographical maps. They are Wardley Maps, invented by Simon Wardley, who is also the founder of Map Camp. This was the first one ever, and I was lucky to have a ticket: there were 250 people filling St John’s, Hoxton, and 250 more on the waiting list.

The conference opened with a tutorial. Each member of the audience received a copy of a long and complicated report on an imaginary technology company. Given not quite enough time to read and digest it, we had to work in groups to turn it into a strategy. Naturally, we failed, because the idea was that we would be in a state of confusion approaching Simon Wardley’s when he was first inspired to invent his maps.

As CEO of a small successful company, he realised that he did not understand how to make strategy, and he had no hope of learning because nobody else seemed to either. There was no way to get better because he could not see what was actually going on. So he came up with the idea of mapping out what a company does and what it needs in a way which is easy to look at and reason about.

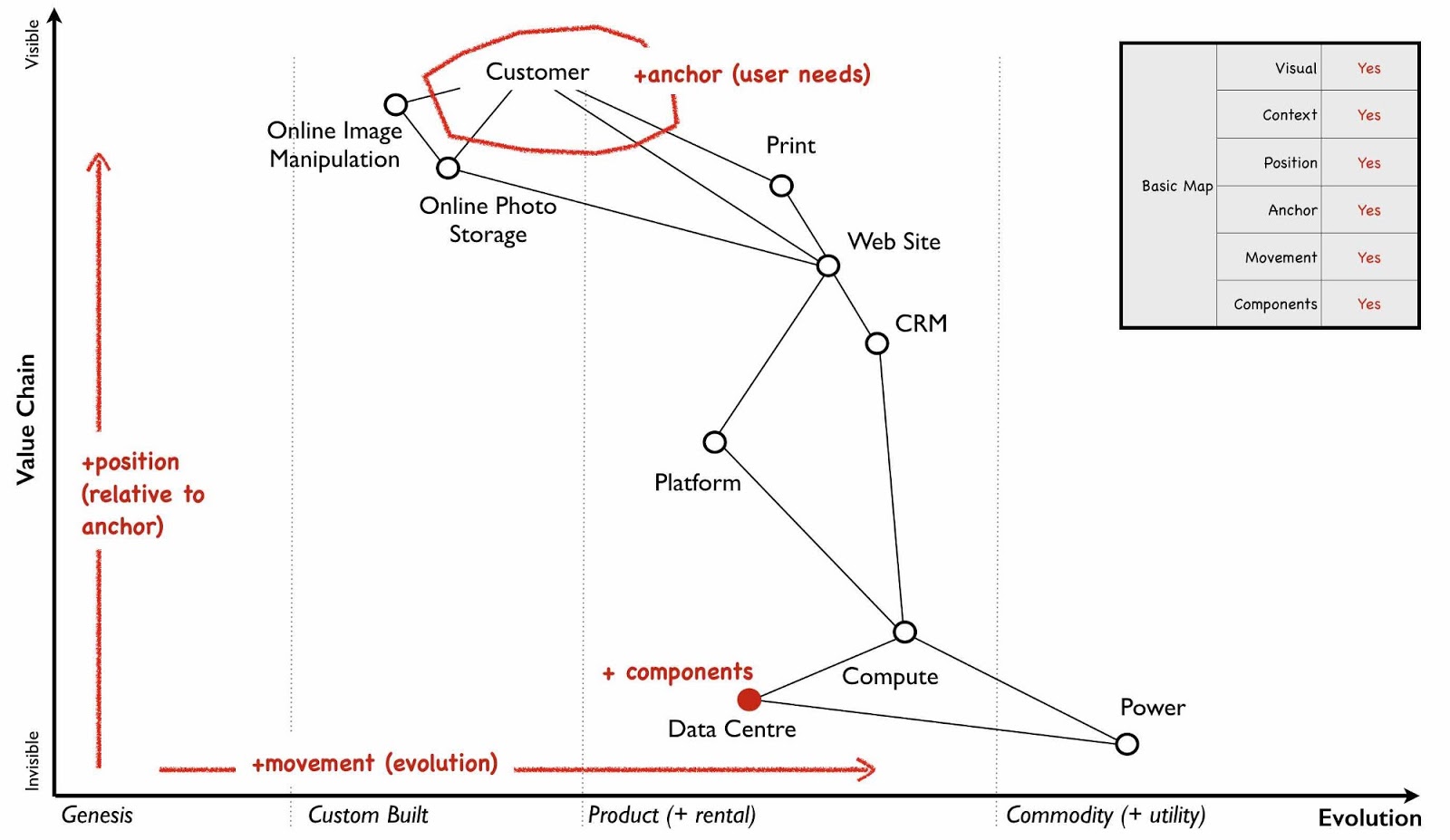

The picture below is what he created. The points hang down from an anchor at the top, in this case, a customer, and each point is a dependency for serving that customer’s needs. The dependencies have dependencies. The x-axis position shows how far along a dependency is on its inevitable drift towards being commoditised: the key insight here is that things on the left tend to move to the right.

Seeing this new way of representing things reminded me of the story of Flatland, where everyone is a 2-dimensional polygon and sees the world as a single flat line. One day a sphere comes to visit and blows the narrator’s mind by revealing that he can look down on him:

When I descended here, I saw your four Sons, the Pentagons, each in his apartment, and your two Grandsons the Hexagons; I saw your youngest Hexagon remain a while with you and then retire to his room, leaving you and your Wife alone. I saw your Isosceles servants, three in number, in the kitchen at supper, and the little Page in the scullery. Then I came here, and how do you think I came?

Terrifying stuff. And there is a warlike aspect to Wardley mapping. The tutorial was peppered with the language of battle: territory, undermining, flanking, firing. Occasionally a sports term crept in: a strategy was a ‘play’, for example. These words feel at home in the world of corporate competition; other speakers during the day were attempting more peaceful projects like rebuilding their IT infrastructure, and the words were less comfortable there. I wondered if this was a limit of Wardley maps, that somehow they only worked as weapons.

Doctrine

Once you have drawn a lot of Wardley maps, you begin to see patterns, which may be used to formulate principles, or in the language of mapping, which is borrowed from Sun Tzu, ‘doctrine’. For example, certain skill sets seem useful at different points in the evolution of a commodity, and this is a common enough doctrine that it has terms to go with it: ‘pioneers’ thrive far on the left, developing original things; ‘settlers’ are the ones who begin the process of commoditization by turning these into products that can be used by others, and ‘town planners’ are the ones who turn these products into commodities, changing the landscape for a new wave of pioneers.

Andy Callow, head of Technology Delivery at NHS Digital, spoke in the afternoon about how he had tried to use these role divisions on his project, and hadn’t yet found a satisfactory way. His Medium post on the subject is worth reading. (Airbnb have had some success with the so-called “PST” approach: there’s an article about it here). Andy Callow spoke of a perceived status gap between pioneers, who are by definition newcomers building the new, exciting thing, and existing staff, who must be town planners because they spend most of their time maintaining things.

It’s a tricky distinction to make, because all three groups need a lot of overlapping skills, not least of which is maintenance. And it is surely discouraging to hear “you are an X, and Xs don’t do this”. But perhaps these things only apply at large scale.

Futurology

Another consequence of finding patterns is that you can use them to try and predict what will happen next.

Simon Wardley pointed out that Amazon, by controlling the lion’s share of application servers on the internet, is uniquely well-placed to map and measure which services and companies are growing fastest. It can then use this information to decide what to build or assimilate next. It is on its way towards an unprecedented monopoly. A talk later in the day by Adrian Cockroft of AWS added some dark strokes to that scenario when he talked about Amazon’s vast and growing AI capabilities, which seem to be eating jobs at a healthy rate. That was nice and sinister.

Another of his insights was that companies can use open source as a means to push their products towards becoming commodities supporting ecosystems, and that like AWS, these ecosystems were excellent ways to entrench and enrich their owners and undermine incumbents. On the other hand, incumbents themselves, like Microsoft, traditionally push back against open ecosystems through fear, uncertainty, and doubt. As an innocent open-source hippy I found the idea that open source can be used as a weapon surprising and a bit upsetting, but of course, it’s obvious when you think about it.

Mapping in practice

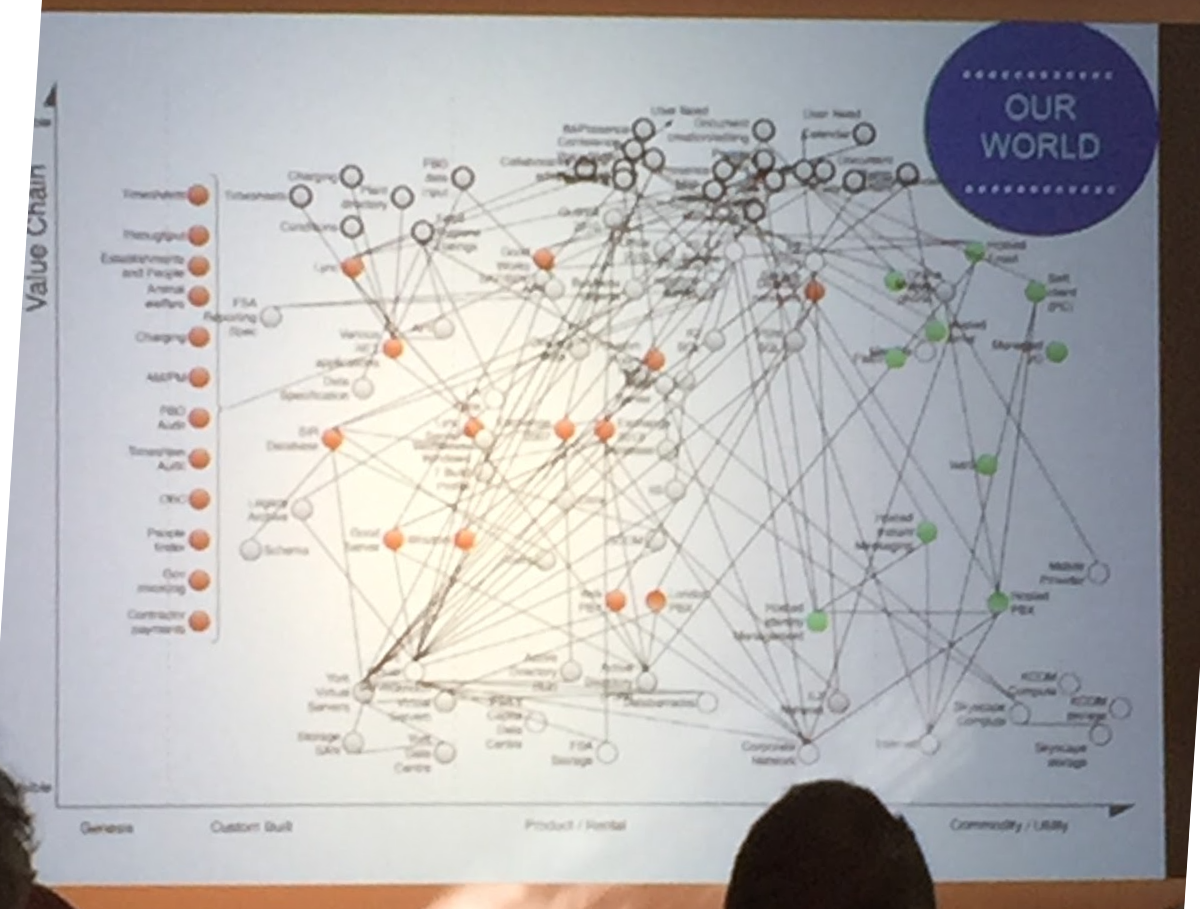

The most striking slide of the day was this one, which came from the Food Standards Agency. It’s a Wardley map covering two of their services.

The audience literally groaned in agony when they saw it, but that shows one of the strengths of this technique: if nothing else, Wardley maps are a powerful way to illustrate complexity.

They can also be an elegant way to lay out dependencies, including extra information about how mature the dependencies are.

This picture reminds me of my uncertainties about how we create these maps. You are free to mix levels of abstraction: an application here, a team there, a building there. This feels like it might lead to peculiar conclusions if not handled carefully. In any case, that the doubt is present is enough to make you ask “do I need a specialist to help me map?” And if you do, then mapping is not the convenient, comprehensible thing we hoped it was, it’s a plaything for wicked consultants.

Maps are seductive, and they have built-in authority. Although being “lost” in business is not really like being lost in the woods, a map intuitively sounds like the sort of thing you need. “The lie of the land”, “the situation”, “the outlook”: the language of navigation is always at hand when we talk about things we can’t see. But it takes conscious effort to remember that your map is not like other maps, and the rocks and trees are actually wobbly, leaky abstractions that may not be where you think they are, or they are, and they’re also somewhere else, and they’re also something else. A map is a radical simplification: powerful in its way, but also mysterious.

As the day comes to an end, we drink fine craft beer under a marquee in the churchyard. It’s dark, and the canvas is flapping, and words like ‘situational awareness’, ‘tactics’ and ‘landscape’ are on everyone’s lips. The mood is happy, with a dash of exultation. This was a small conference beautifully executed.

I have doubts. Perhaps this is Flatland, and Simon Wardley has discovered a sphere. Or perhaps the whole thing is made up. Anyway, there’s no way to check: and as ever, it’s almost certainly the case that the conversation matters more than the artefact.

We clink our cans like happy little polygons.