The hidden fundamentals of digital transformation in healthcare

The people side of digital service development and rollout isn’t the soft side – it’s the hard bit

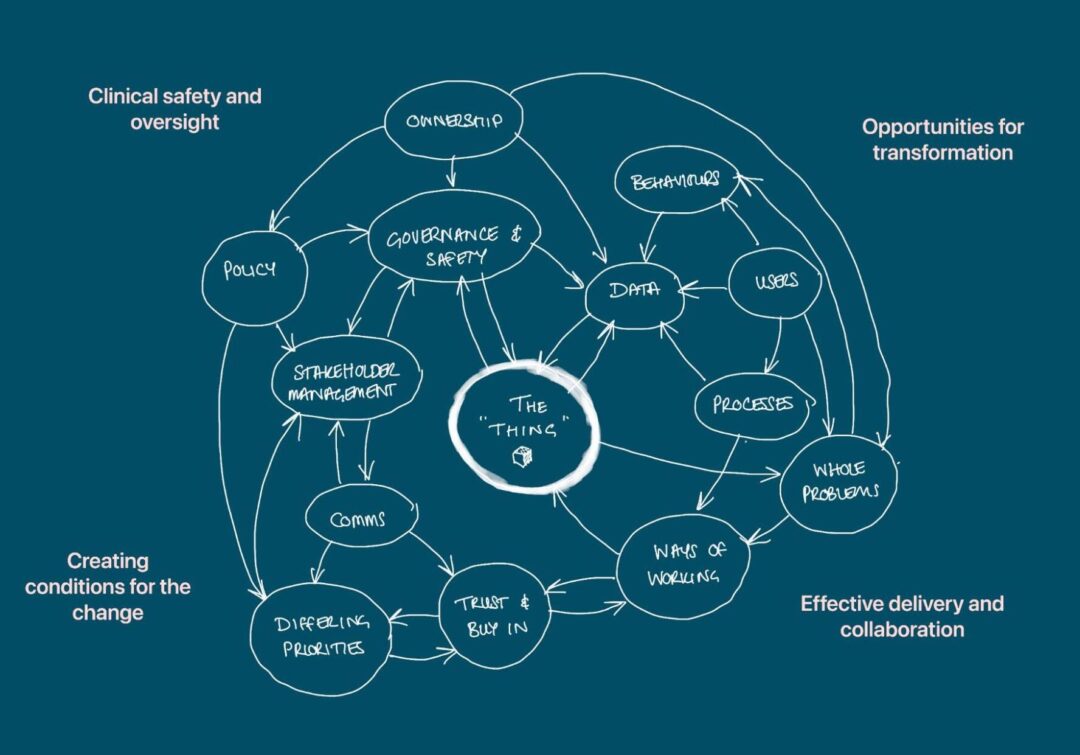

In the first post in this series, my colleague Marianne talked about why designing ‘the space around the thing’ is critical for transforming healthcare. Products alone just won’t do it.

We’re still in the thick of our work with NHS England and our understanding is evolving as we help shape the future of the NHS breast screening service. We’re navigating a live, complex national-to-local rollout — and it’s teaching us a lot about what real transformation requires.

In this follow-up, I want to zoom in on one of the ideas Marianne mentioned – how trust, influence, and relationship-building are just as critical as good technology, especially in complex and semi-devolved systems.

The technology matters — but it’s not the whole story

There’s no question that the technical challenge is real. Designing digital services that work for a national screening programme in a local environment isn’t easy. You have to integrate with diverse existing systems, handle local variation and consider patient safety. Not to mention managing, and often decommissioning, legacy systems alongside.

But what’s become increasingly clear is that technology alone doesn’t drive transformation. As more decision-making power is devolved to Integrated Care Boards (ICBs), national teams can’t assume one-size-fits-all delivery. Success is really all about the people impacted by the new product – the admin and clinical staff who use it, and the screening participants who experience it.

Change doesn’t land just because it’s technically sound. Or even operationally sound for that matter. It lands because people trust it, understand it, and feel part of it. So development needs to be done in partnership, and the quality of the relationship with those partners is critical.

Mandation is not a silver bullet

The question of whether or not the new breast screening products will be mandated comes up regularly in meetings. I suppose it’s because it’s tempting to think that a national mandate equals instant compliance and therefore impact. But there are numerous examples of failed attempts to implement new healthcare initiatives through mandation1.

Mandation can help with consistency. And it can be a springboard for those on the fence about the change. But it doesn’t eliminate the need for genuine buy-in. To really engage in the changeover process, people still need to believe the new system will improve their work and support better outcomes — and that requires well-planned comms, transparency and two-way dialogue, not just instruction.

We’re already seeing how this plays out in practice, in the absence of clarity about when our new systems will be mandated. Thanks to coordinated comms and targeted stakeholder engagement, we’ve seen a great level of initial interest from Breast Screening Offices (BSOs) in working with us. And we have secured our first private beta partner to start testing our solution for digital invitations.

In the complex structure of the NHS, senior decisions and actions are sometimes needed to create the conditions to effectively engage stakeholders in this way. Part of the messaging that led to the initial interest mentioned above came from a senior decision to communicate that we would be moving away from the existing breast screening system.

This kind of top-down, bottom-up tension can be tricky to navigate. It takes a strong understanding of the overall landscape and sound judgement on when to dive in with local teams, and when to influence further up the chain.

Stakeholder mapping isn’t admin, it’s strategy

The NHS stakeholder landscape is complex. Roles, responsibilities, and influence don’t always follow an obvious structure. That’s why we’ve learned to prioritise stakeholder mapping as an essential activity, not a side task. And for this project, it was key to initially research and map the whole system to be able to identify the stakeholders. This exercise was also foundational in helping us understand early potential barriers to rollout for further investigation.

Having access to the right conversations has transformed our progress. Getting an invite to the heads of public health meeting enabled direct discussion and feedback on early adopter selection; reducing the risk of blockers later in the process. Similarly for the regular breast screening programme managers’ meeting, we were instantly able to unlock an initial wave of early adopter interest (an area the team had found challenging) for our product to be used during the screening appointment.

Shared purpose is the anchor

With so many moving parts — digital, clinical, policy, operational — the only way to maintain alignment is by staying rooted in purpose. Whether we’re talking about the vision for digital communications in breast screening or the full end-to-end screening journey, everyone needs to understand why we’re doing what we’re doing — and that why needs to make sense from their perspective.

For a public health lead, it might be equity. For operations, efficiency. For product teams, user experience. The vision is the same, but the language and incentives often vary.

Enthusiasm is only the start

When we speak to potential early adopters, generating excitement is often the first hurdle — we’re not the first people to talk to them about improving breast screening systems over the years. But the real test is when the initial interest gives way to practical questions: What would being part of a private beta really involve? What are the operational challenges? How do we manage the risk?

Supporting teams through that shift from curiosity to commitment requires careful, two-way engagement. Leaving something behind after the initial conversation helps ground the discussion and lets people reflect after the meeting. We’ve created several tools for this already, from slide decks to a ‘costs saved calculator’. The latter in particular has been invaluable for securing buy-in from Trusts – another key stakeholder in the system who often manage IT infrastructure and certain supplier contracts on behalf of the BSOs.

And what about that change fatigue and scepticism?

Honesty really matters. We’ve found it far more effective to be upfront about what’s known, what’s still evolving, and what participation in a private beta really means – partners need to devote time and effort to the work. It’s about shared goals, transparency, and commitment to working through the hard stuff together.

Understand your users…in 3D

It’s all well and good to have positive conversations with specific BSOs who are potential early adopters. But at some stage, the roll out will need to pick up pace, start onboarding more BSOs at once, and deliver the support needed to go with that. We’re working closely with the newly created pathway team to understand the wider breast screening operating landscape. That means conversations with the BSOs. All 77 of them.

It’s not a quick task, but absolutely vital to planning an effective roll out – both from a user perspective, and the central operational logistics to make it happen. And this isn’t just about understanding local processes, structures, systems and contracts. It’s also about gauging attitudes and appetite for change. You don’t always get that from something like a survey.

Reading body language, and between the lines – that relational intelligence is critical. You can’t phase a rollout properly if you don’t understand the terrain you’re trying to roll across.

The bottom line

The people side of digital service development and rollout isn’t the soft side – it’s the hard bit.

Building something new, in public, with people who are rightly cautious is hard. But it’s also the work. We’ve learned that building trust, managing expectations, coordinating communications, and understanding local variation are not “extra tasks” — they’re the foundation of successful delivery.

What’s next?

What I haven’t covered in this post is how the end user – the screening participant – fits into the people part of the space around the thing.

In our next blog post, we’ll dig deeper into how to move beyond product thinking and design for whole problems, which rightly revolve around the participant — including all the offline and human elements that shape what a good service feels like.