How to use existing infrastructure to enable digital transformation in healthcare

How can we use infrastructure to our advantage – to guide development, unlock opportunities and deliver a new service with long-lasting impact?

During our work to transform the national breast screening service with NHS England, we’ve had to work with core NHS infrastructure that sits outside of our immediate digital teams. From clinical assurance to hospital IT systems, supplier contracts and beyond, if you want to develop and launch a new digital service, there are many structures to navigate and processes to follow.

The timescales, interdependencies and national vs local nuance can be overwhelming. And the processes and relevant stakeholders involved are often hard to clarify. It can feel tempting to try and avoid them at all costs.

In this penultimate post in our series on ‘the space around the thing’, I want to focus on how we can use this infrastructure as material to work with, rather than a barrier to work around. After all, these mechanisms are the underlying fabric of our health system, ensuring safety and continuity for us all. If we try and design outside of that logic, we’re surely destined to fail.

So how can we use this infrastructure to our advantage – to guide development, unlock opportunities and deliver a new service with long-lasting impact?

The key, as ever, is in the preparation. As Sir Ranulph Fiennes once said, “There’s no such thing as bad weather, just inappropriate clothing.”

That means:

- Up front detective work to untangle and deeply understand the relevant infrastructure that shapes the possibilities for a new product. For example, knowledge of the existing supplier contract landscape will help you plan when, how and where to roll out a new product.

- Shifting mindset to appreciate the opportunities with the existing system rather than seeing the boxes to tick and people to please (although that still has to be done). For example, strategically timing clinical assurance hazard workshops to maximise learning and positive input as opposed to setbacks.

Here’s some of that thinking in more detail, rooted in what we’ve learned so far.

1. Understand how the system holds itself together

Before you can change a system, you need to understand how it sustains itself.

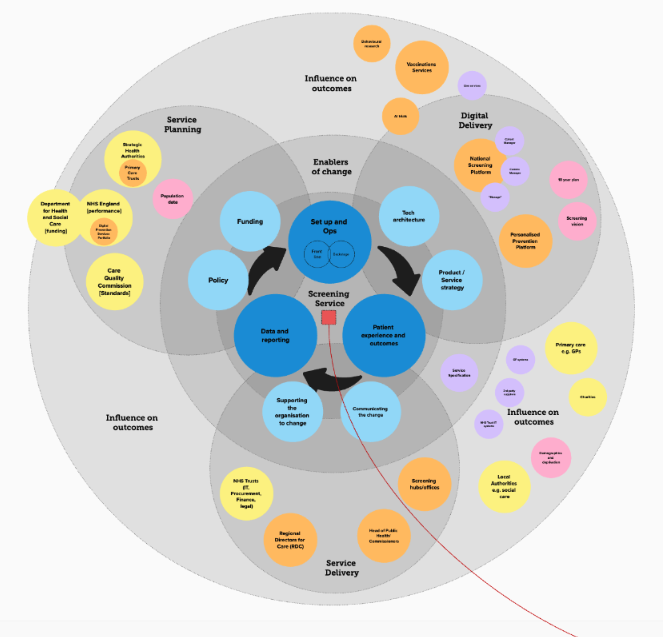

In our work on breast screening, that has meant intensive, in depth learning around information governance, clinical safety, IT and the accountability that surrounds each product and process, on both a national and local level. It’s not just about who signs off decisions, but also what risks those decisions exist to manage. Our team mapped out the system early on in the project and it’s paid dividends down the line for planning and prioritising.

Understanding the less formal processes has also been key, but perhaps even harder to get a handle on. So much of this is implicit institutional knowledge and not necessarily documented anywhere. I talked about the importance of a solid stakeholder map in an earlier post on the hidden fundamentals of digital transformation in healthcare, and it’s invaluable here. Who needs to know or actively feed in on what and when?

It’s been interesting managing the interplay between NHS England and local NHS operations in breast screening offices (BSOs). Despite having central information governance and clinical sign off, so far we’ve needed to go through similar local processes too. And naturally in a devolved system like this, there are different local quirks. It all adds to the information you need to have available, not to mention the timeline. Understanding this helps improve rollout planning.

Once you can see how those connections hold the system together, you can start to work out where movement is possible – how you can work through it rather than around it. Small shifts made in the right places can create meaningful change without destabilising what keeps people safe.

2. Use governance as a framework for change

Governance is often seen as something to ‘get through.’ But when you work closely with governance teams during the design process, it becomes a framework for change – both for your product and the process itself. It gives new ideas legitimacy and creates confidence and accountability around your work.

In practice, this is about involving clinical safety officers early, testing assumptions collaboratively and documenting decisions transparently in decision logs and design histories. It’s also about understanding and using what’s already there e.g. data conventions like SNOMED codes.

My colleague Matt Lucht has written in more depth about some concrete steps our team has taken to work more closely with assurance colleagues in response to the disconnect between the process and agile working. It’s a great example of the value of testing small process changes within existing governance routes rather than creating parallel processes.This collaboration has led to both improvements in the process for teams to come and more meaningful outputs to drive our progress in digitising communications with participants in the national breast screening programme.

4. Treat legacy systems as assets, not obstacles

Legacy technology is often described as a problem to be solved, but it’s also a record of how services have evolved and adapted over time.

While we recognise the limitations of NBSS (the digital system underpinning breast screening) in today’s world, it has supported the service for over two decades. It’s also one of very few single systems used to deliver a service across England. Groundbreaking in its day.

So approaching this task from what we can learn from NBSS, and how it can practically support us to transition to a new system, is key.

As Ron Bronson writes in Design as Repair, design isn’t always about starting with a blank sheet of paper or jumping on the latest technology — it’s about understanding what already exists and where the improvements lie. Addressing the fundamentals before the bells and whistles.

Understanding how users interact with NBSS has given us invaluable knowledge about how people really work: the shortcuts, dependencies, and workarounds that have kept care running. We have to learn from those patterns, identifying what’s worth retaining, and building a new service that respects that existing stability.

Change built this way is more reliable and solid — because it connects to what’s already trusted.

5. Rolling out at the system’s rhythm — and knowing when to shift it

In healthcare, rollout is rarely a single switch being flipped. It’s an ongoing process of alignment between national ambition, local delivery, and everything in between.

So understanding how and when the system can move — and where a well-timed nudge can create momentum is really important.

Early in our work on the programme, we conducted a deep dive into the contractual landscape for letter printing and postage across all BSOs. Mapping suppliers, contract types, and start and end dates helped us plan the rollout of digital invitations in a way that is both ambitious but achievable.

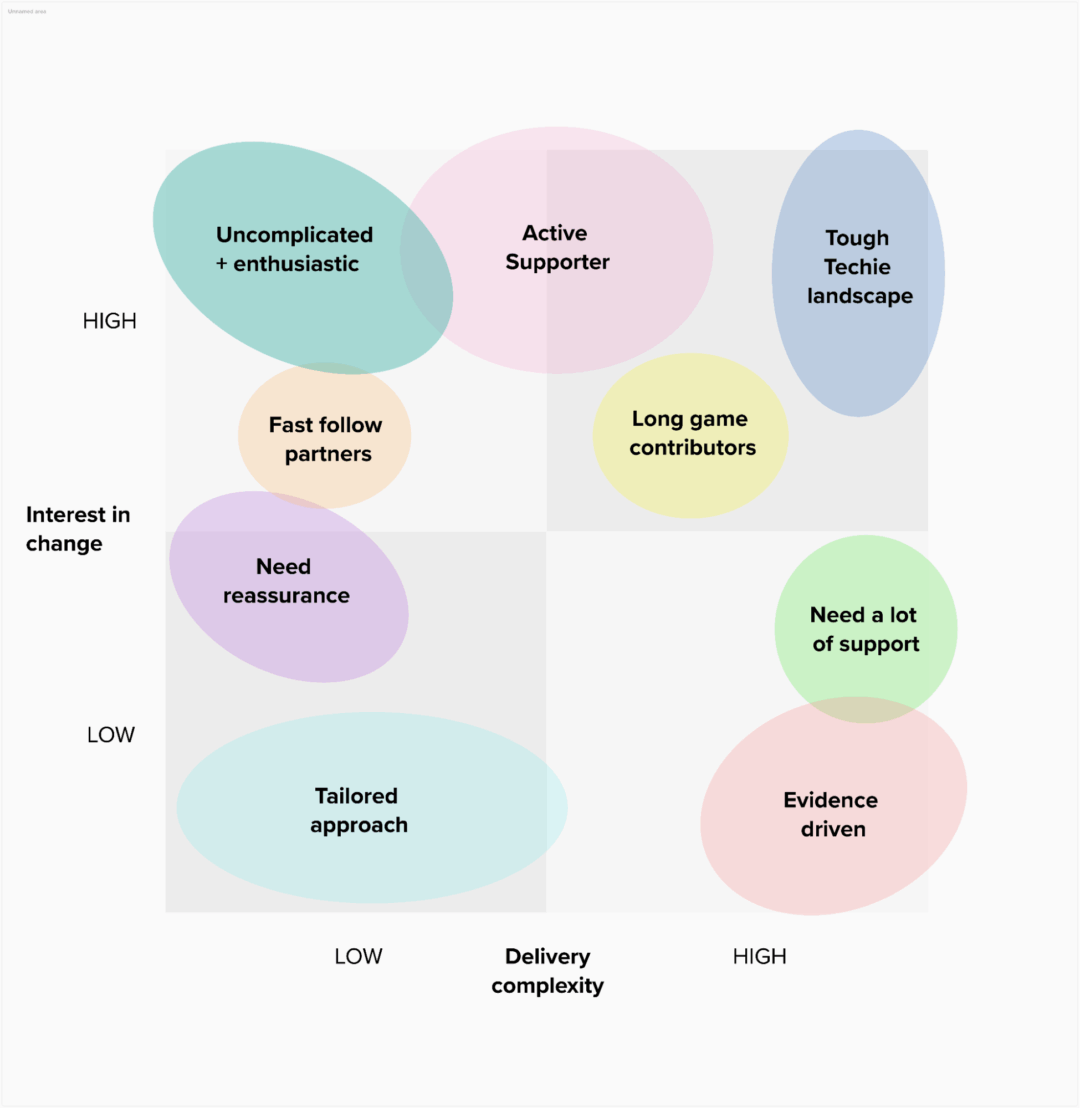

We also carried out work to understand the rhythm and process around updating the breast screening service standard and guidelines, in the knowledge that these need to be updated to support the transition to a new service. On a macro level, you can’t transform a service if you don’t understand the landscape you’re trying to change. Individual interviews with a significant number of BSOs has helped to give us a sense of BSO interest and capacity for change alongside practical considerations for transition such as the behaviours of their Trust, or complexity of their delivery context.

Our change landscape map, based on one-to-one interviews with Breast Screening Offices

Using information gathered at these interviews to map our understanding of the change landscape is helping us plan the transformation responsibly and sustainably — not by waiting for perfect conditions, but by designing around real ones. For example, taking into account our own team capacity, we can now ensure that we don’t try to tackle two highly complex Trusts at the same time.

The goal isn’t simply to move fast or slow, but to move intelligently: in ways the system can absorb safely and sustainably, while still making visible progress toward change.

So that’s the ‘what’, now what about the ‘who’?

By treating NHS infrastructure as material to work with, we open up space for smarter, safer and more sustainable digital transformation. But this only truly works when the right people are in place to make the change happen.

So in the final post of this series, we’ll zoom out to explore how the scale and nature of the NHS shape the kind of leadership and teams we need to nurture to deliver real transformation — and make it stick.