How a Digital Services 3 procurement could look

On Tuesday, I went to a supplier engagement session run by the Digital Marketplace team. It was great.

The government CTO, Liam Maxwell, kicked the session off. Several of the team behind the Digital marketplace, G-Cloud and the Digital Services framework then explained what was going on, and described their thinking.

I tweeted most of this as it was going, so you can have a look on Twitter for more about that, and what was said.

After the talks, there was a co-design session where we (as suppliers) were asked to design a high-level process for buyers to choose an appropriate supplier for their project. We were broken out into smaller groups for this, each group facilitated by one of the GDS/CCS team. Our table had some good discussions, especially about the tension between making the pipeline of work visible (good) but not having a process so open that hundreds of companies compete for every project (bad, because very wasteful).

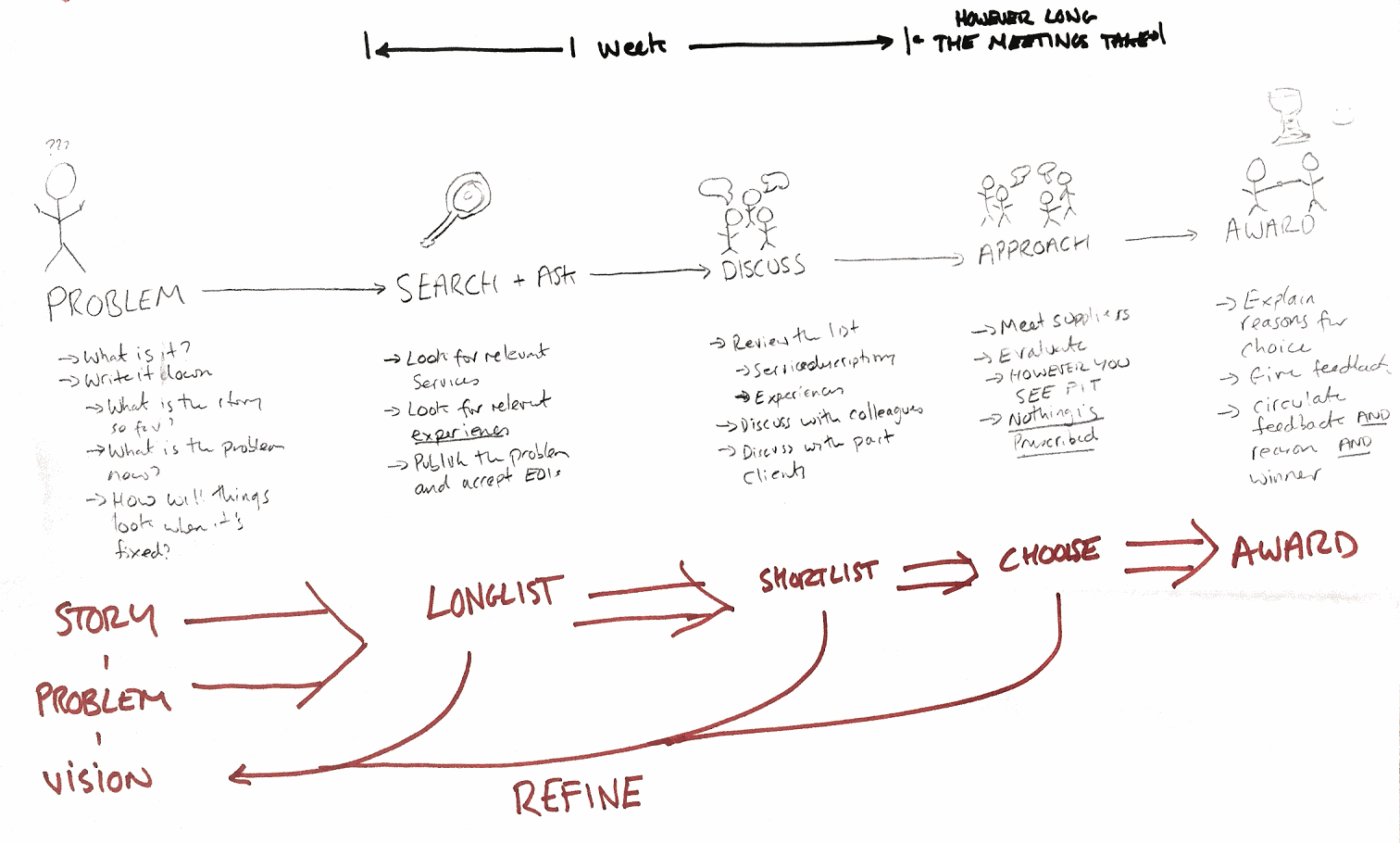

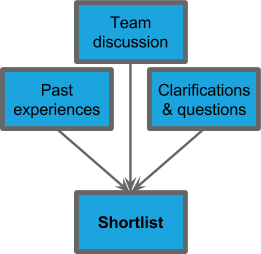

As part of that session, I did a quick diagram to describe how I think the process could work, which we refined as a group. Here’s what we came up with.

Given the time restrictions, this is necessarily pretty high level. Also… messy. So I thought a tidied-up, better-explained version might be a good thing: hopefully, one that others can contribute to and help improve.

This process is heavily influenced by the G-Cloud selection, and is intended to give delivery teams a lot of freedom – in particular, to chose evaluation methods that work for them. It’s also supposed to line up nicely with the Service Design Manual and the Service Standard – which all Digital Services projects should align to.

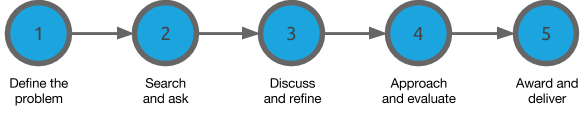

So here it is:

1. Define the problem

Most of the time, procurements for digital services start with the solution that the buyer wants, rather than the problem that they’re trying to solve. This is a bad way to go about things.

For any service of non-trivial complexity, there is no one right solution. So there’s no amount of work that will ever allow an “ideal” solution to be understood – let alone described or specified. That’s why the fifth GDS design principle is “Iterate. Then iterate again.” The world of the formal specification is long gone, and it’s broadly recognised that iterative approaches lead to better software – at least, whenever there’s uncertainty and change that needs to be accommodated.

So why, in this brave new world, do we still procure based on patchy descriptions of untested solutions? This can only lead to bad outcomes.

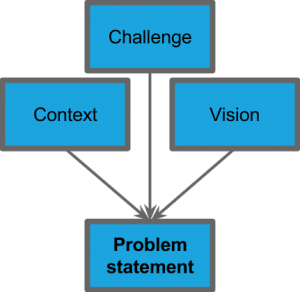

Instead, government should procure people to solve problems. The process should start with the buyer explaining the challenge they have, the context (aka: the story so far) and their vision: how will things be different when the project is live and working?

This problem statement also needs to be iterative. As the buyer moves through the procurement and the project beyond, they will learn more and gain insights about their problem. We need to make the best of that – not hide it away. So, throughout the procurement (and after it), the problem statement should be kept up to date, and potential suppliers made aware of changes.

Finally, it’s important not to procure everything at once. At the start of a project, the procurement should just be for some strategy work, or a discovery phase. And there should be regular opportunities to go back to the market and see if a better option is available. But the statement of the problem should always be as complete as possible, and the vision should be a user-centred description of the outcomes the project will ultimately achieve.

We need to start with problems, not solutions.

2. Search and ask

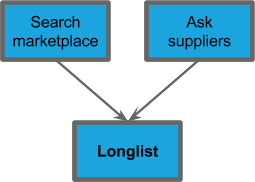

Next comes a longlist. The buyer should assemble a list of potential suppliers, preferably broad in their range of services, experience and values. This list should be generated from two main sources: a marketplace for digital services, and a digital services pipeline.

Search marketplace

Exactly as G-Cloud has service descriptions for the various products and services available through it, Digital Services Framework suppliers should write service descriptions that explain what they do, and how they do it.

These descriptions should explain key parts of their process, talk about their values and their commercial approach. Where appropriate, they should describe the skills and experience of their teams, and the technologies they’re familiar with.

Some of this information should be structured so that buyers can filter based on it, but effective free-text search should be the priority.

With all of this information available, buyers should use the marketplace to create a list of suppliers they think can meet their needs.

Ask suppliers

Effective though G-Cloud’s process is, one of its weaknesses is that it leaves suppliers at the mercy of effective searching. This is not a very good thing, and it sorely limits transparency because suppliers don’t know what’s being searched for.

So, as soon as the buyer has a problem statement, it should be published. Suppliers should be able to search the list and add themselves to the longlist for projects they are interested in delivering.

The process needs give suppliers information about upcoming projects, and buyers clarity about what suppliers can do.

3. Discuss and refine

With the longlist in hand, the process moves forward to shortlisting. It’s essential at this stage for buyers to have a relatively free hand to shortlist the suppliers they want and for that part of the process to be as light-weight as possible. As a supplier community, I think we must accept that it is not proportionate or cost-effective for buyers to give detailed consideration and feedback to every unsuccessful longlisted company.

For me, being longlisted but not chosen to move forward seems much the same as when a potential buyer checks out dxw’s website but then moves on, having not seen what they wanted. If I get the opportunity to ask what they were looking for, then I will – but I wouldn’t expect them to be proactive in giving us feedback. It’s too early in the process for that to be reasonable.

So how should they do it?

First, the buying delivery team should discuss the list as a group, identifying companies they definitely want to approach, and ones they don’t.

Second, the process needs to put buying delivery teams in touch with their counterparts in other parts of the sector. If you’re building something, you need to talk to others who’ve built something similar, to gain the benefit of their experience. If you’re thinking about using a company, you should chat to some of their past clients to see how things went.

Some of this information should just be made available for buyers to easily review – it’s vital that government buyers share their experiences. So while we must avoid facile approaches like star ratings and ebay feedback, we must find good ways for buyers to describe and feed back on their experience – good and bad – in structured ways. And in ways which offer the suppliers some right of reply.

Third, where there is some point of uncertainty about a company’s offering or capability, it should be straightforward for the buyer to ask for clarifications.

The process needs to include mechanisms for buyers to talk to each other, and learn from their past experiences.

4. Approach and evaluate

By now, the buyer will have shortlisted a few suppliers (perhaps 3–5) who they believe will be able to help them. At this stage, the framework needs to give buyers a great deal of freedom to decide how to evaluate.

There are some fundamental requirements that the framework should lay out. Like using Most Economically Advantageous Tender (MEAT) to evaluate responses, and ensuring that whatever process used is fair, open and transparent.

But beyond that, buying delivery teams must have a free hand to choose evaluation methods that are a good fit for their project and its user needs.

If a team with some hefty UX work decide that the best evaluation method is to ask for a single side of A3, giving a compelling description of a past project, they should be free to do that.

If a team with a seriously tricky integration want to set suppliers a small technical challenge, they should be free to do that.

If a team with an exceptionally complex problem want to ensure that the supplier’s staff have the skills and values they need to work effectively together, and so decide to conduct a series of interviews, they should be free to do that.

No single approach fits all solutions, and attempts to force all digital projects through one evaluation methodology will fail – no matter how well considered, or well intentioned. We need to get away from the familiar comfort of the requirements document, and allow buying teams to be free to choose suppliers however they see fit – within the rules – with procurement professionals on hand to support and guide them.

I think procurements should be awesome. I think they should be engaging, challenging, exciting and fun! I think tackling a new problem and getting stuck into a new set of ideas and challenges is fantastic, and I’d be very surprised if that feeling wasn’t shared by most people who create digital services for a living.

If we’re ever going to get to procurement approaches that provoke people’s curiosity and get the best out of all involved, we need processes that are effective and enlightening – not a chore that’s dreaded by buyers and suppliers alike. That’s going to require a lot of experimenting and learning, and that’s what an open approach to evaluation can give us.

Buying teams need to be able to evaluate suppliers using whatever methods are most appropriate for them, their problems and their users.

5. Award and deliver

Finally: award. Tell the winning supplier they won. Also, tell them why they won. And tell everyone else, too.

It’s really important that the process is as transparent as it can possibly be. So, when a winning supplier is chosen, the buying team should write a few paragraphs explaining what won it for them. This should be distributed to all of the shortlisted suppliers, along with individual feedback on their bids.

Procurement decisions need to be transparent: not just the details of the award, but the reasons for the award, too.

Addendum

It’s vital that as much of this process happens in the open as possible. It’s also vital that the GDS/CCS team have the freedom to evolve this process in whatever way seems best. This is why the Digital Marketplace is such an important project.

This entire process – from beginning to end – should be mediated and administered by the Digital Marketplace. All decisions should be recorded there. Everything that can be published, should be published. All management information should be recorded there, and made available.

The pipeline of upcoming procurements and list of awards should be there, free and available for all to see. Every problem statement should be available for people to see, and kept up to date, along with a list of all the procurements related to it.

The best way to prevent abuse in these processes is transparency. The transparency we have now is really pretty opaque, relying on people’s understanding of arcane process, obscure publications and time-consuming FoI requests. Let’s get past that.

Let’s design a process we can all be proud to participate in, make procurement the most open bit of government, and invite everyone to have a look.

When they’re reassured and impressed by what they see, we’ll know we’ve achieved something big.