Helping HM Coastguard understand how to raise awareness of coastal safety

If you were enjoying a coastal walk and someone fell down a cliff, who would you call?

If you were enjoying a coastal walk and someone fell down a cliff, who would you call? In an emergency we know to call 999, but which emergency service do we then ask for? Police? Fire? Ambulance?

HM Coastguard is the emergency service which provides 24 hour search and rescue at the coast and at sea. When someone’s in trouble, they send out helicopters, lifeboats, and coastguard rescue teams, coordinated from 12 control rooms around the UK coast.

For any emergency at the coast, you should always call 999 and ask for the Coastguard. However over 50% of people surveyed by the Maritime and Coastguard Agency (MCA) don’t know who to call if someone’s in trouble at the beach, coast, or sea. This is a problem. In an emergency, getting the right service to the scene as quickly as possible could make the difference between life and death.

Not just rescue and response

In 2018, the Coastguard responded to 22,600 incidents. But rescue and response is only part of the challenge they face. Last year 128 people died around the coast of the UK, with 73 people drowning on or near beaches. If people understand the risks and prepare themselves, many of the tragic deaths at the coast could be avoided. This is also part of the Coastguard’s role to increase safety awareness at sea and around the coast.

As a transformation partner with MCA we did a discovery with the Coastguard to understand how a website could improve awareness of their role as an emergency service. We also considered how they might use their expertise in sea safety to positively influence user behaviour when they’re visiting the coast.

What we did

To understand people’s awareness of the Coastguard and their understanding of safety and risk, we conducted in-depth qualitative research with members of the public. This research built on the quantitative insight from the annual Water Safety survey commissioned by the MCA. The interviews generated thick descriptions which provide context and the meaning behind participants’ actions so we could start to understand their behaviours.

We also conducted pop-up research at Southampton International Boat Show. Pop-up research is great for interviewing a large number of people in an informal setting, using short and focussed questions.

What we discovered

The Water Safety survey showed that people are unsure of what to do or who to call when there’s an emergency at the coast. The qualitative interviews we conducted revealed one of the reasons for the ambiguity: the majority of participants didn’t know who the Coastguard were or what they did.

Participants identified the police, fire, and ambulance as emergency services. Some incorrectly identified the Royal National Lifeboat Institution (RNLI) and mountain rescue as emergency services, but few were aware of the role of the Coastguard. Even though it’s one of the four emergency services and has existed for nearly 200 years.

This is problematic not only for the Coastguard, but for members of the public who get into difficulty and need assistance. Ringing 999 is only part of the solution. Asking for the correct emergency service could be critical to the response time.

People tripping or falling into the sea, usually while running or walking, accounted for more than half of coastal deaths in 2018. Although participants were able to identify the common hazards associated with the coast, they both underestimated the risk of it happening to them and failed to identify this common cause of death.

Where to find safety advice?

There’s an appetite for safety information from the public. An analysis of social media and online forums found that people were asking for information, advice, and guidance about safety at the coast, but were unsure where to get it from. Trust in a source was an important factor for participants.

Even for those who do things like kayaking, climbing, and hiking in coastal environments, the UK is generally perceived as a safe place by participants. One participant identified themselves as “risk averse” but had contrasting understandings of risk depending on the level of knowledge of a location. Familiarity of a place and its hazards can be influences on people’s evaluations of risk.

What we recommended

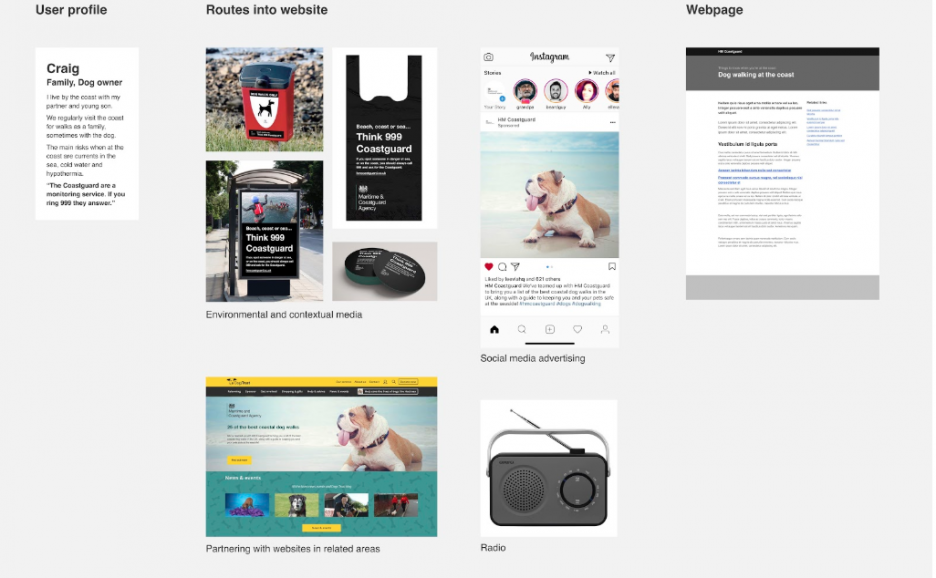

The general public are not connecting emergencies, coastal risks, and questions about safety with the Coastguard, our research found. And a website alone would not address the problem.

Not all risks are to people in the water, as cliff walkers and dog walkers are a high risk group. Our research found that these groups aren’t actively seeking safety information about the coast so their exposure is limited.

Building on existing safety messages, the Coastguard could incorporate other media into their campaigns to provide alternate routes into a website. This could include targeted environmental and contextual media such as on dog poo bins or bags, partnering with websites in related areas, or sponsored posts on social media.

A Coastguard website would be most successful when viewed as part of a longer user journey and a broader content strategy. It must work as a way to provide the specific safety information and reassurance members of the public are looking for but needs to be supported by online or offline messages elsewhere.