6 things we learned by designing services for experts

Things to think about when building services for experts in the public sector

This blog post is based on a talk we gave at the Service Design in Government Conference.

dxw has worked on a number of projects in government departments to help design and build services for both the public and for civil servants. We’ve been reflecting on the differences, and similarities, when building services for the public compared to experts. So we based our talk on what we’ve learned by designing services for civil servants.

When we were preparing our talk, we realised that we’ve built services for lots of different people who’re not strictly civil servants. People like coast guards, housing officers, healthcare professionals, judges, school inspectors, and many more. So we decided to tweak our focus so it became: 6 things we learned by designing services for the people who deliver them.

Theme 1: best practice can get in the way of experts trying to do their job (Louise)

I worked on a project for the Ministry of Justice (MOJ), for probation practitioners, called Managing a Supervision in the Community. Probation practitioners work with people on probation to help them comply with the terms of their probation and support them in whatever way they can. Like helping them find work and accommodation.

The service was being built as probation practitioners were using a dated and clunky database to record their interactions with people on probation. So we worked with MOJ to prototype a new service.

For those that may not know, content designers working on services are there to help guide users through a transaction or a task using simple and consistent language. So, as a content designer, how did I manage to make it harder for experts to use a service?

Lesson: best practice needs to be considered in the context of your service

You might be familiar with this guidance from GOV.UK which is good, solid advice:

The first time you use an abbreviation or acronym explain it in full on each page unless it’s well known.

It’s content design 101, right? Unfortunately for me, it was the wrong thing to do.

For probation practitioners, risk is a big part of their role. For every person on probation, they have to assess the risk they pose to themselves, the public, and to staff.

So it’s really important information that has to be really accurate and really prominent as well. There’s not a lot of content but it’s one of the most important pieces of information that probation practitioners need to do their jobs.

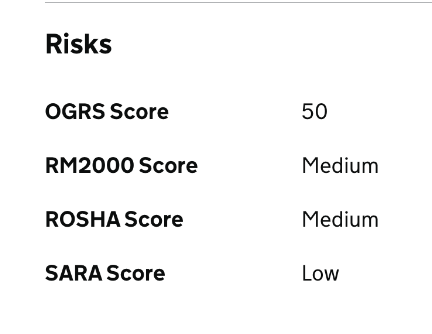

This is a close up of what the risks section looked like. Looks pretty hard to read, doesn’t it?

Starting at the top, these are what the scores mean:

- Offender Group Reconviction Scale (OGRS)

- Risk Matrix 2000

- Risk of Serious Harm Assessment (ROSHA)

- Spousal Assault Risk Assessment (SARA)

When I started working on this service and saw that this was how the risks were displayed, I immediately thought about best practice and how I should write out these scores using their full names. You can imagine how this looked on the screen – loads more words but in my opinion, it was much clearer to read with fewer acronyms and initialisms.

So when we started usability testing, I felt quite confident that probation practitioners were going to appreciate how clearly all these scores had been written. It turned out to be a very humbling experience.

During the first testing session, I heard a probation practitioner reading out all of the words in the risk section and for every risk score, they said things like, “Oh, that’s OGRS” or “That’s ROSHA” and it made me realise that I was making these experienced and very busy people, read double the amount of words. This meant that I was slowing them down and adding to their mental load. Something that content designers really shouldn’t do.

And it’s why the risk scores were written using acronyms and initialisms. They may not be easy to read but they help the experts that the service was built for.

So a big lesson for me is that best practice needs to be considered in context and it isn’t a law that you need to abide by. It’s good to question what applies when designing for experts compared to the general public.

Theme 2: acknowledging the role of legacy technology and people’s brains (Louise)

Legacy technology systems are like zombies…they survive on brains.

This quote is from a blog post by our colleague and Lead Technologist, James, who’s written an excellent blog post about legacy technology.

In the post, James talks about how processes and systems were traditionally done with people and paper. When we started using technology for these processes and systems, organisations often replaced the paper with computers. This means information still flows between systems via people’s brains. Which for me, in the context of designing a service, means you need access to those brains to be able to build something useful and user-centred.

Whenever we’re building a service to replace legacy technology, I feel like we should try and start afresh and not spend too much time looking at the legacy technology. But it can often be difficult for people to detach their job and their responsibilities from the technology that they use.

And that’s why it’s really important to understand what the frustrations are with the current system and what experts need, rather than just critiquing the legacy technology.

Lesson: you need lots of time and access to be able to feast on the experts’ brains

As I mentioned earlier, it’s important not to rely only on best practice to build a new service. To tap into these brains, you need to talk to the experts. A lot.

At MOJ, these were some of the ways that we tried to extract knowledge from people’s heads:

- we used surveys to find out the level of knowledge that the experts had around the terminology in the existing service

- we interviewed multiple people to find out what they need to do in their roles. This meant we found out what they have to legally record when they’re meeting with people on probation, what’s useful for them to know, and what information is important when a colleague or someone on duty is taking over their caseload

- we also did workshops to understand the information that probation practitioners need to know before, during, and after appointments with people on probation

- model office testing or day in the life testing where we created realistic tasks and scenarios, and tested them with probation practitioners in person. We also created interruptions to reflect a typical day for a probation practitioner

The main lesson here is be prepared to spend lots of time getting information from experts. It’s so important to get access to the people that you’re building a service for.

Theme 3: seeing the beauty in time pressure for us as practitioners and for the people delivering the service (Chanelle)

One lesson for me is seeing the beauty in time pressure. Time is so important when working with people.

dxw work varies from longer projects that can last years to smaller projects that can last days. I’ve been involved in a few projects where a designer was only needed for a short period of time. But it turned out to be rewarding for me, as well as working well for the people delivering the service.

Lesson: apply time pressure to yourself even when you have time

I worked as an interaction designer for a project about mental health where the team had 9 days to design, test, and build a new feature to help users create and maintain better connections in an online community. We jumped straight into an ideation workshop on day 1 and started prototyping by day 2. We made a rough plan, stuck to it, and launched a new feature by the end of the week.

In 9 days, we ran 8 research sessions and built 10 prototypes. But we were able to filter out the noise you often get when you have “too much time.” Shorter projects are an opportunity to ask not only the right questions, but the most important ones. And you tend to structure things so they get “straight to the point” which makes them a lot easier to understand. Our Community Managers in this case, really valued this way of working.

There can be downsides to time pressure but when managed with a strong plan, the right amount of pressure can become momentum. As an interaction designer on this particular project, it meant we skipped the sketching and wireframing stages and went straight into high fidelity designs. This isn’t our usual practice. We normally start small with sketches, low fidelity prototypes, no colour involved.

I worked on a similar project for the Department for Education (DfE) but as a service designer this time. I was asked to join the project for 5 days to help the team create a service map.

There was lots of reading and lots of talking, but we were able to produce the start of something that the team had been trying to do for years. It showed what collaboration can do in a short amount of time. If we didn’t have just 5 days, would we have made this progress?

It’s normal to think you can produce something better with more time. But I would argue, with complete focus in your mind and your diary, an element of time pressure can help you produce the best work.

What does this mean for delivering services? We don’t always work on short projects. Right now I’m working with MOJ on something longer term. However time pressure can still be applied by prioritising parts of the project and setting timeframes for these that turn pressure into productivity.

I like to allow myself some freedom to be both intuitive and impulsive, to take 2-3 quick steps forward even if you then need to take one step back. You’ll probably have heard the saying “it’s a marathon not a sprint”, being good at the marathon and the sprint makes us better all round athletes!

Theme 4: Understanding the role of culture and ‘ways of working’ within our work (Chanelle)

Culture is something we don’t always think about enough. We often go into projects with an idea of what we want to deliver. It could be a digital tool, a new process, or a tech solution. But what about the people part?

The people part is the thing that you figure out on the project as you get to know the teams you’re working with. Building relationships, giving people the freedom to express themselves and introducing new ways of doing things, can go a long way before, during, and after a project.

Before making the thing, designers, practitioners, the team who are delivering the service, and end users need to feel connected.

Lesson: the answer isn’t always digital. Tech is easy, people are hard

I worked on a project with Ofsted to design and improve the process of allocating inspectors into schools. We worked hard thinking about what the future service would look and feel like. We held workshops, ideation sessions, alignment meetings, and design critiques. All the stuff you would expect in a design journey. But we started to realise that these daily interactions and changes to people’s routines were also having a positive impact.

The teams started talking more, even the people who were usually quiet in meetings. The client was introduced to new design thinking tools which had a knock-on effect on how and what they presented in meetings. They saw the value in service design practices, something that wasn’t present in the organisation.

This “invisible” stuff can have a big impact. But the invisible is hard to measure. Things like culture change take time and draw meaning not from numbers, but from the change itself. To quote our favourite friend, James again, “the problem is very rarely technology (it’s usually organisational)”.

All design problems are human problems. So we find ourselves asking: how might we spend more of our time and effort to support the transformation, the cultural change?

Arriving with a good methodology and having good ideas is not enough to produce lasting change. All the services we work on are built and operated by people. If we understand people, we understand culture and ways of working. Users will have a better experience if the people building and delivering the services do.

Theme 5: what we do affects people. Both positively, and sometimes negatively (Morrighan)

Inside and outside of dxw, I spend a lot of my time advocating for and talking about mental health, emotional literacy, and the importance of practising empathy, as individuals and designers. I want to mention how important it is to think about the impact of our work on civil servants, both the positives and the potential negatives.

We can ask a lot of people. Civil servants are often under immense pressure and dealing with heavy workloads. This context is really, really important. It matters.

As designers, we always aim to do good and make positive change. But not taking into account civil servants’ fraught contexts means there’s a risk we miss the potential unintended, and maybe negative, consequences our work might have.

Put yourself in this civil servant’s shoes: you’re working extra hours to keep up with your workload. Often using legacy systems or tools that are inadequate and make things difficult. BUT you’ve got used to that, they’re familiar, and you’ve devised your own ways of keeping on top of things. Then suddenly someone who isn’t an expert in your field arrives, starts unpicking your processes, telling you what’s wrong and how it could be better.

Worst of all, they ask you to give up a chunk of your precious time to help with research. To sit through unmoderated testing, be a participant in private betas, and take part in everyone’s favourite: Miro board workshops. Yet more things on your plate.

“Lets turn off your legacy systems”

We often find ourselves turning up and saying, “how about we turn off your legacy systems?” As Louise mentioned, the process of replacing or moving away from legacy systems is complex. There’s a massive practical and emotional attachment to them. Change can seem terrifying and like an awful lot of work.

“Try this new application instead”

More often than not, we’ll also be asking people to use start using a new application, tech, or digital tool. To follow a new process is a big ask for any user, particularly those working under pressure. Learning a new tool demands time, effort, and attention. All while still managing your existing workload.

There’s also an understandable worry about the impact in future on someone’s role where we’re looking to optimise or automate processes. Big changes like these are inherently complicated and with them comes a range of stresses.

Lesson: respect people’s time and think of different ways to engage

This is something we’ve seen in a recent project with DfE. We’re working with the department to help deliver massive transformation. We’re supporting them to move away from multiple layers of legacy systems and build one centralised system instead. Some of this work has been going on for some time now, before we joined the project.

It’s important we don’t waste our busy stakeholders’ time by asking them to reshare or redo work that already exists. And if we do, we’re clear about why. So, with that in mind, at the start of this project, we spent a lot of time digesting and collating the important things that had already happened.

We have formed a close relationship with our Product Manager who was around before we arrived, so we can sense check things we might want to research and find out if that work exists somewhere in the backlog. We’ve shadowed people so they don’t have to show their whole process again (and again).

And we’ve worked on new ways to engage with users to make sure we don’t take up too much of their time. We only engage when we need to or use asynchronous methods of engagement like Microsoft Teams chats.

We know moving away from legacy systems is complex, and asking users to buy into new applications, processes, and tools is a difficult and emotionally complex and draining ask. So we’ve worked hard to communicate not only the immediate value the work is adding to people’s roles, but also the longer term goals and opportunities.

This is also an opportunity for people to ask questions and add their thoughts on the future of the service, the new application, and their role.

“How about we change your way of working”

We explore, research, and unpick the way users work. And we suggest ways to, hopefully, make them more efficient and effective. But, in doing so, are we asking users to potentially change everything they know about their day to day job?

Ultimately, we might turn up, and say something like, “You’re the expert here, but…” This can be incredibly difficult, frustrating, and tough for some service providers.

Lesson: they’re the expert in the room, use and respect their knowledge and experience

In our recent project with the Department of Levelling up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC), we found ourselves in this situation. The department was going through internal and governmental restructuring at the time. And was under a huge amount of scrutiny from ministers. That in itself, without any other factors, seems stressful enough for anyone, right?

The project centred around helping the department structure, plan, and implement planning reforms and the levelling up agenda. Quite a hefty task. A pretty big part of this was doing a deep dive into the way things work now, finding out what’s not working, where those major risk areas are, and where things could be improved.

One of the most valuable things we did in this project was getting the right people in the room together. We facilitated conversations and group discussions, and came up with ideas collaboratively.

We started by speaking to each team individually, hearing their perspectives, plans, pains, frustrations, and hopes. Then we put all those individual teams on a call to play back what we had heard. This was the first time they’d ever all sat in a virtual room together to look at the big picture.

We then supported them in discussing problem areas and potential solutions. The result came from their hard work and ideas. It came from them. Not us. They, the experts in the room, did the thinking, we just gave them the space, opportunity, and tools to do it. Putting the power back in their hands and giving them ownership.

Design with civil servants, not for them. Hear their expertise and know how far to challenge, when to stop, and the right way to push things forwards.

Lesson: be empathetic

Be empathetic. Take a step or 2 in your client’s shoes.

Theme 6: what the audience thought

We asked the audience which theme resonated with them most (it was theme 5) and to share any other things they’ve learned. So here’s some more thoughts on building services for experts.

Think about how you show up

- Be gentle

- It gets harder before it gets easier

- Compassion is better than empathy. Empathy can be bad for your health

- Invest time up front to fully understand experts, their language, and the service

Consider where experts are coming from

- Employees can be proud of being experts on legacy systems

- People don’t like change but most people want to do the right thing

- You have to break established patterns and create new guidance for experts

- They’ve often been thinking about how to make things better far longer than you have and have often already tried and failed to improve the services themselves, you can learn from the workarounds

- They may be experts in their policies and current ways of working but rarely are they experts in managing change and they might feel very vulnerable with the prospect of change

Some helpful things to remember about experts

- The experts in the room aren’t always the experts

- “Experts” exist on a scale. New people join teams too and the balance is tricky

- Speak to the caseworkers not the managers

- People don’t often step outside of their roles and the earlier you embed experts in the process, the more buy-in you get

- Sometimes the level of knowledge is diluted when the knowledge transfers from person to person

Don’t forget:

- The role of the service in helping new experts learn the organisational landscape

- To factor change management processes into projects as well as replacement services so that users are prepared for the change

- That you can never ask all of the right questions, sometimes you have to learn through delivering

- Design thinking can often increase the scope of a service