Using design to address whole problems in healthcare: beyond the feature list

Delivering value to users won’t come from building and shipping features in isolation

This is the 3rd post in a blog series about the work that goes into the “Space around the thing”. It follows on from “The hidden fundamentals of transformation in healthcare.”

dxw has been working with NHS England in the Digital Prevention Services Portfolio for the last year. This work contributes to one of the three pillars of the 10 year health plan “sickness to prevention.” When we first started working in digital screening, one thing became obvious very quickly: this service was big, knotty and complicated.

There are multiple teams, focused on different areas of screening and on delivering specific features for specific users. In a complex environment, with multiple influencers and priorities, it’s easy to lose sight of why we’re really doing the work. Delivering value to users won’t come from building and shipping features in isolation. It comes from understanding and addressing whole problems. This includes thinking beyond products.

For example, screening offices are focused on increasing uptake of screening. In digital screening we are delivering digital first invitations – ‘Ping and Book’. How someone receives their invitation to take part in screening is just one part of a larger effort to encourage people to get screened. This effort includes locally led communication campaigns, GP practice and local authority involvement, IT systems, good data, follow up processes, public trust, local priorities, clinical safety, the postal service and more.

The parable of the blind men describes the impact of thinking in features over problems. One man feels the ear, and thinks it’s a fan, another feels the leg and thinks it’s a tree… Neither have the whole picture to understand what’s in front of them is actually an elephant.

Whole problems vs isolated features

“Step one is to orient the system around outcomes. For example, reducing health admin and improving patient outcomes.” – James Plunkett

The second point in the GOV.UK service standard tells us to “solve whole problems” for users. This is much harder than it sounds when you’re in the depths of product development.

Just like downloading and using a banking app won’t make you better at managing your money, we can’t expect a product to do all the heavy lifting if we want to see real transformational change. What products can do is reduce administrative burden, improve safety, data visibility and usability, and reduce the cost of training and onboarding users through more intuitive, accessible design standards. By giving someone back their time, or by making data more available, what opportunity is there to improve outcomes and think differently about how a service could be delivered?

Product-led thinking often starts with, “what functionality can we ship?”; Service-led thinking starts with, “what outcome are we trying to achieve, and what needs to shift in the system to make it real?”. Both ways of thinking are necessary for delivery, and they need to work together to ensure the functionality we’re shipping is contributing positively to the outcome we’re trying to achieve.

Product definition should be couched within the bigger picture, helping teams remember what outcomes their work is contributing to. ‘Ping and Book’ is part of the story of ‘Making it easier for participants to take part in screening’. When we look at digital first communication in the context of the bigger picture, what else might we see opportunities for?

- The process around people who don’t attend an invitation

- The user needs for cancelling and changing appointments

- Recognition of someone’s history with cancer and how that might affect their attitude towards screening

- Previous negative experience with screening and how that might affect their behaviour

- Where and when we offer appointments to people who have other commitments, anxieties or constraints

- How we can build trust and awareness of the benefits of screening in underserved groups

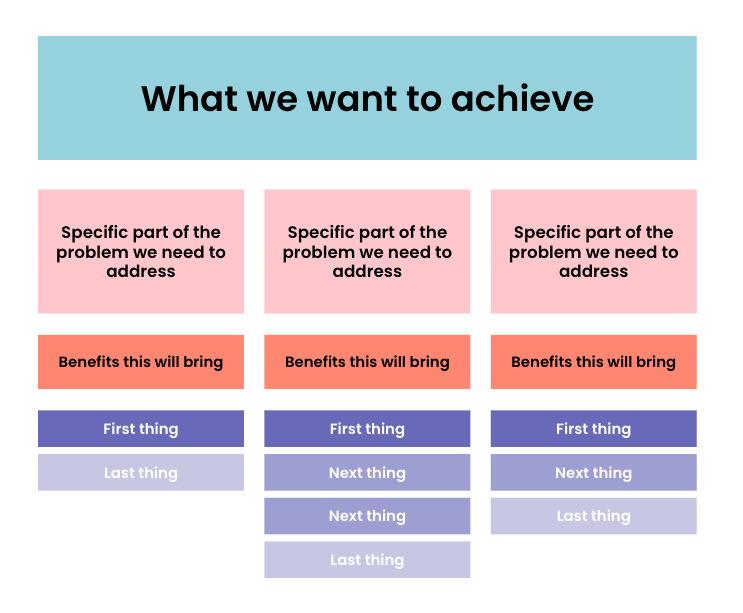

Solving these goes beyond introducing new products and tools. It’s also much more than one team could hope to solve alone. It requires buy in and collaboration with multiple groups, systems and processes. Being clear about outcomes is the first step towards making it easier for groups to collaborate, because they are joined by a common aim. This level of collaboration needs strong leadership who can help teams work through the layers of competing priorities, supporting closer working between organisational siloes, be that digital or clinical.

Making sense of complexity

In public services, we often have multiple multidisciplinary teams working towards similar policy goals such as reducing reoffending, reducing homelessness or building more homes. These goals are usually well articulated. Where it gets messy is when we go down a layer into the delivery teams, who are identifying slices or chunks of user needs (often based on who’s funding them, or the fault lines of their organisation). Jane touches on the idea of ‘Shared purpose is an anchor’ in the previous blog post; this purpose should help delivery teams have autonomy to shape their work, and identify opportunities for reuse or join up with other areas of an organisation.

It can be remarkably difficult to stay aware of what each team is focused on delivering. This risks duplicated effort solving the same problem over and over. It also increases the chances that the service experience will feel fragmented to users, as different teams deliver different parts of the whole. In an earlier post on working in the Ministry of Justice, I share an example of how zooming out, and focusing on purpose helped us prioritise areas of value, and identify opportunities for join up and reuse.

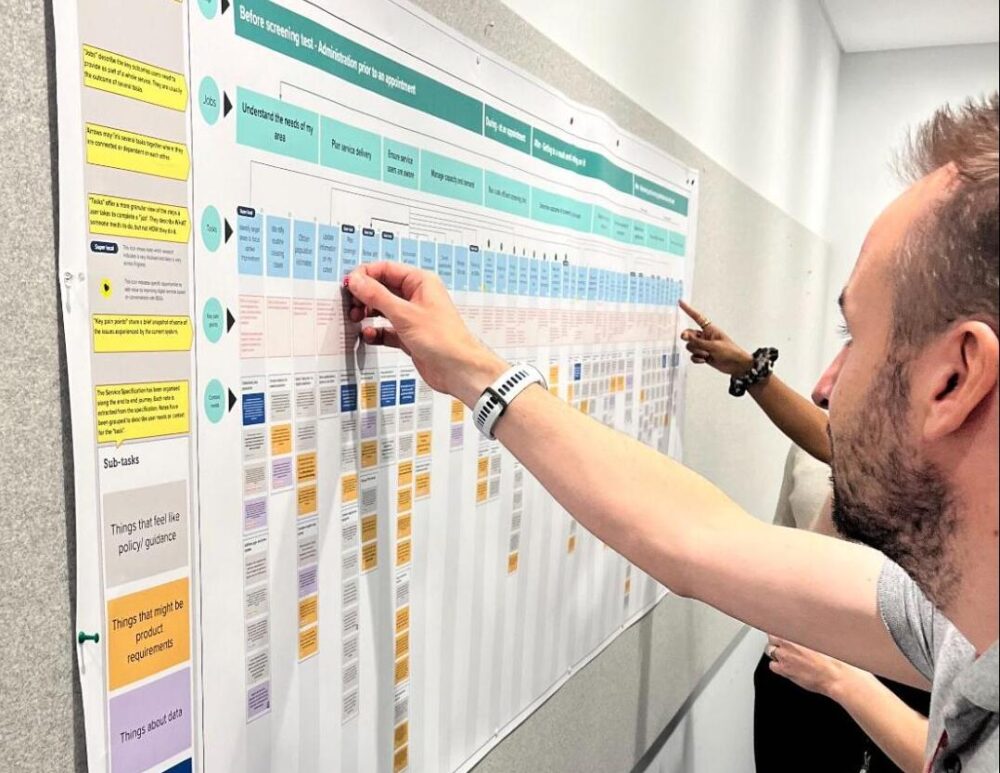

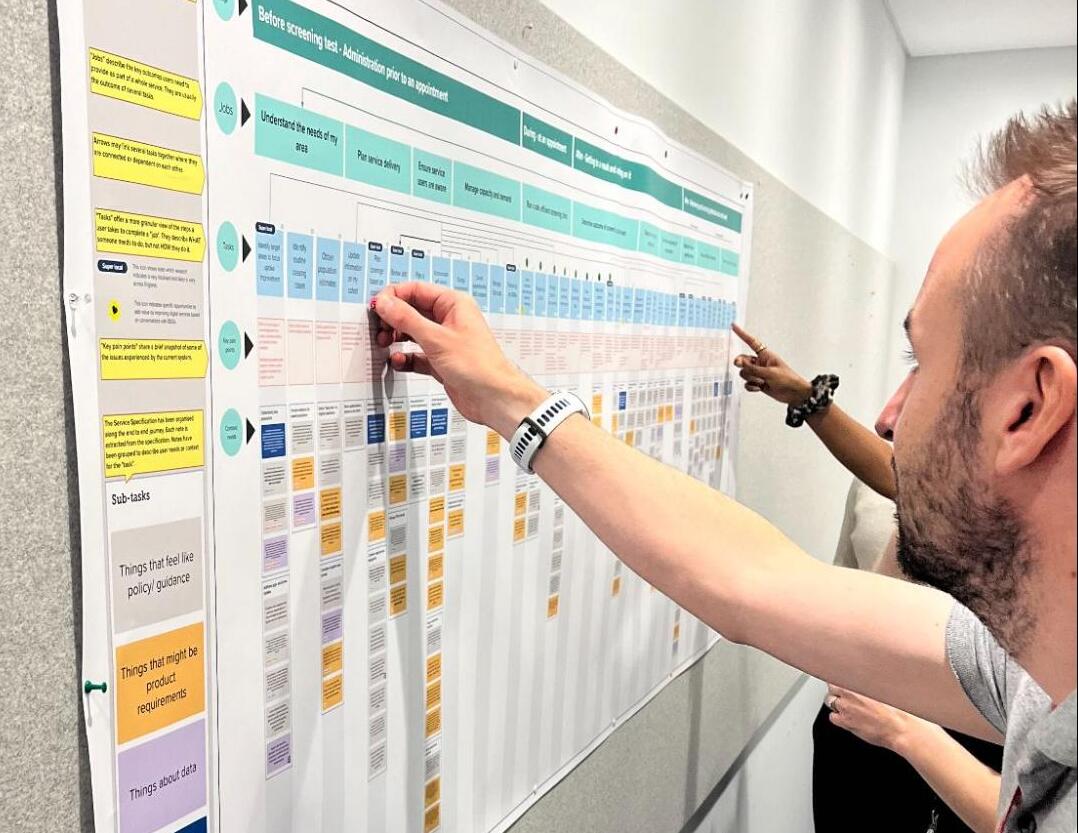

One of the most valuable activities we’ve done recently is mapping who’s doing what across breast screening. That work quickly surfaced overlaps and gaps:

- multiple teams addressing the same outcome or user need, from different perspectives

- unclear ownership for parts of the journey such as onboarding, training and guidance (where consistency is key)

- dependencies between teams – where they may be designing the same part of the journey but for different users

- gaps, where some outcomes have no team assigned to support that need

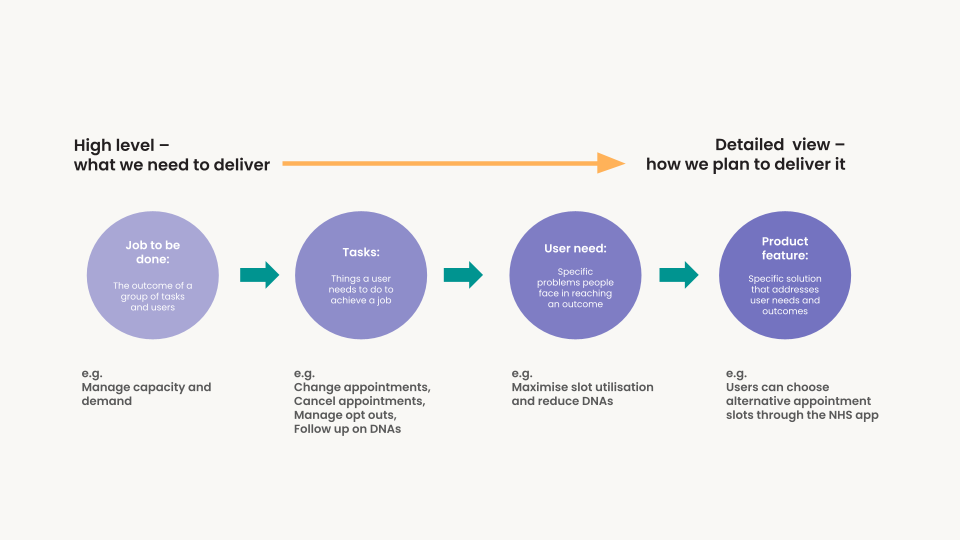

We got to this view using the ‘Jobs to be Done’ theory. Using the screening policy documents as a guide, we were able to describe the end to end through the lens of outcomes for service users. This approach helped us shift focus from features and products, to why we’re building things.

This kind of mapping doesn’t just create a nice diagram. It changes conversations. It lifts us out of our siloes by highlighting our place in the bigger picture. And helps us think about whether what we’re building is the thing users actually need.

The relationship of JTBD to product feature/capability

Bringing teams together around whole problems

Being clear about what outcomes we want makes it easier for us to communicate outwardly about change. As per principle 7 of Good Services, users and stakeholders shouldn’t need to understand the internal structures of the organisation to understand what we’re delivering and why. We need to work harder behind the scenes to de-mystify the work, reduce digital ‘gatekeeping’ and make it easier for others to contribute.

Ensuring you have service designers in your organisation can help with this. Employed at both delivery and strategic levels, they offer valuable skills to help join the dots across the organisation. To do this effectively, they need support to access the right people and forums that can amplify their recommendations in support of outcome focused work.

Service design complements the work of Product and Delivery by contributing insights and recommendations that might influence priorities and make sure we are designing the right thing. This helps teams trace what they are building now, next or later to the long term goals, which in turn makes it easier for us to communicate when users might expect to see change for the areas they care about.

Digital products are essential, but they’re only part of the picture. It takes a lot of work to align teams, stakeholders and groups on the right level of problem to solve.

This is why we’ve focused on this as part of the ‘space around the thing’ – a way to approach managing and communicating delivery in complex environments. To really deliver outcomes government and the general public expect, we need to think and act in service of whole problems, not feature lists.

This is the shift we’re advocating for in digital transformation: less “what feature can we ship next?” and more “what problem are we really solving, and who needs to be part of making it work?”