What service designers do (part 1) – generating understanding and facilitating decision making

What does ‘service design’ actually mean?

This is the first of 2 blog posts focused on the value created by our service designers at dxw.

When you think of service design, journey maps, blueprints and canvases may spring to mind. But service design is about much more than a few tools and methods.

Google ‘service design’ and you’ll find a number of definitions:

Wikipedia: “Service design is the activity of planning and arranging people, infrastructure, communication and material components of a service in order to improve its quality, and the interaction between the service provider and its users.”

Nielsen Norman Group: “Service design improves the experiences of both the user and employee by designing, aligning, and optimizing an organization’s operations to better support customer journeys.”

And GDS: “Service design is the activity of working out which of these pieces need to fit together, asking how well they meet user needs, and rebuilding them from the ground up so that they do.”

Add an image search to this and you’ll see a range of different tools and approaches, (presumably to help you reach the goals of these definitions).

We often wonder if any of these definitions actually help those less familiar with the discipline understand where a service designer fits within a team? Or how that role changes as the project progresses? Or if they get a sense of what a service designer actually does day to day? Because it can either seem a little abstract… or that we just ‘make maps’.

In response to the question, ‘what is service design?’, starting with some of the common elements from the descriptions above you could say:

- Our goal (much like the rest of our the dxw team) is to improve the quality and effectiveness of services

- We do this by joining up the understanding of user needs, and of business processes/constraints, across the whole journey

- There are a range of methods and tools that we can draw on to reach those goals.

Of course, each service designer has their own strengths, backgrounds and specific interests, just as developers might be proficient in different programming languages. Here are some of the core outcomes service design supports, based around a number of simple questions.

1. What’s going on? Generating understanding

It is impossible to do good design without understanding user needs first. At dxw, we work closely with user researchers, business analysts, and sometimes technical architects, to identify the needs of users. We equally focus on the needs and constraints of the organisation, and the ecosystem it operates within, including the technology.

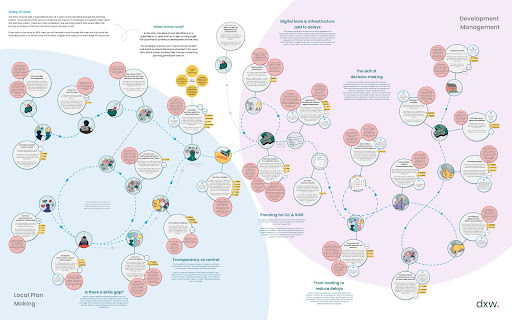

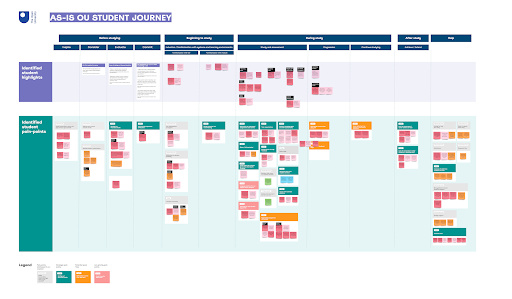

We may visualise this understanding using typical design outputs such as personas, archetypes, user journeys, ecosystem maps, process flows and technical diagrams. The value of each of these things is in generating a shared understanding of who we’re designing for, and the constraints we need to operate in. There’s also value in the fact that they’re created collaboratively.

A service designer may build on this understanding by drawing connections between the pain points experienced by users, and the operational structures set up to deliver services. We’re likely to explore these connections more broadly than the initial service/product/department who initiated the work, given our ‘outside-in’ perspective. We do this by identifying any offline or “invisible” interactions that contribute to the overall experience of a user, and what happens before the service and after it.

An example of an invisible interaction could be the role of service contract management teams (who procure private companies to deliver government services), and the SLAs they agree with suppliers (such as how many days a service can be unavailable). This directly influences how a service delivery team works, and what they might need to measure (for example the number of days used connects to what is invoiced and reported on to policy makers). Other “invisible” interactions could be those that happen offline, through other channels, or by alternative actors, sources and means.

The value of generating understanding through service design includes:

- Creating an accessible narrative that helps those outside of the project engage with the team’s direction and ambitions.

- Identifying connections, actors or touch points that may be useful to explore.

- Identifying opportunities that exist within the whole ecosystem.

2. What does this mean? Facilitating decision making

Products and services do not exist in isolation. Users can have varied and complex contexts and needs. A core skill of any service designer is being able to operate at different levels of detail, depending on what’s needed by the team. For example, they may zoom out to show where your product sits within the wider context of products and services that users will be navigating. Or they may zoom in to details of the front stage interactions and backstage operations for a particular user journey.

Dealing with this complexity often means teams need to set priorities, and focus on an approach that provides the most value to users. Service designers help with sense making of insights by working through decisions with the team to ensure they align to overall strategic objectives. This helps everyone stay aligned, and focused on the outcomes we want to achieve, and ultimately helps foster good decision making.

In practice, this will usually be team workshops and synthesis sessions, which produce things that help connect outcomes of team activities to what we feel this means for the project. Often the process used to reach those things, those maps, diagrams or other illustrations, provides value of its own by encouraging teams to explore, discuss and prioritise together.

The value of service design here looks like:

- Generating ‘Just Enough’ understanding to make sense and enable decision-making.

- Making some of the invisible (such as support staff and their processes, a user’s “offline” activities, or the service structure), feel tangible, so that teams and stakeholders can act on the insight.

- Bringing together stakeholders to discuss opportunities, and agree ways to address challenges.

Our second post (coming next week) will look at creating a vision and designing for services’ current reality.