Working with Drinkaware to help people cut down drinking (part 1 of 2)

To help people improve their relationship with alcohol we needed to surface their needs

We’ve been working with Drinkaware. Their vision is to reduce alcohol-related harm by helping people make better choices about their drinking. Drinkaware asked dxw to help them understand how they might evolve their digital and offline offering to encourage and support long-term behaviour change.

This is the first of 2 blog posts. In this post we explain how we developed a more detailed understanding of user needs which provides a new perspective on how to support people. In our 2nd post next week, we’ll talk about our approach to designing services for something as complex as alcohol and drinking behaviours.

Statistics are useful but not enough to make effective design decisions

As an organisation, Drinkaware doesn’t lack research. They have engaged research partners to help them segment a large and complex audience and so understand where to focus their efforts.

For example, they run an annual, UK wide survey called the Drinkaware Monitor. In 2017 they surveyed people aged between 18 and 85 online investigating drinking behaviours at a national level. The results helped them prioritise 2 segments to focus their services; broadly speaking, on people who are heavier drinkers over the age of 45.

They also run focus groups to shape and test concepts for their campaigns like drink free days.

From a digital product perspective, over half a million people have downloaded the Drinkaware app so far. And over 10 million people visited their website last year.

These numbers along with more granular detail tell us that Drinkaware is reaching a lot of people. But are the ‘reach statistics’ and market segments meaningful enough to make effective service and product decisions?

Making numbers more meaningful. Reconnecting with real people to make better design decisions

Drinkaware is looking to help people make positive changes to their drinking habits that are sustainable in the long run. To help people improve their relationship with alcohol we needed to surface their needs; to understand what a life-time of drinking looked like; what people struggle with when it comes to cutting back; and what drinking less in a sustainable way meant for different people.

So to help Drinkaware reconnect with people we needed to complement the numbers and quantitative segments with in-depth qualitative work. We also knew that we had to step away from using medical jargon to encourage people to talk naturally about drinking and alcohol. This would not only help Drinkaware create content that’s more optimised for search and so is easier to find and digest for users, but also create content that’s easy to understand by the people who will use it.

What we did

After some desk research and a kick-off session with the Drinkaware team we had clear questions to guide our work:

- who are the users and what are their needs? How should we think about people outside of segments?

- what are the biggest design opportunities for Drinkaware?

- how can we help Drinkaware build and support their products in a more agile way in the long run?

Considering the research Drinkware had already done and the aspiration to support behaviour change we conducted 12 in-depth sessions with an element of usability testing with older heavier drinkers (categorised as drinking at increasing or high risk according to the official AUDIT-C screening test).

For the contextual part of the session, we took a long-term approach to understand where they are now, how they got there and what drinking less meant for them. This way we were able to stay open to new ways of framing the problem and allow space for people to tell us how they see their drinking and uncover their underlying behaviour, needs and challenges.

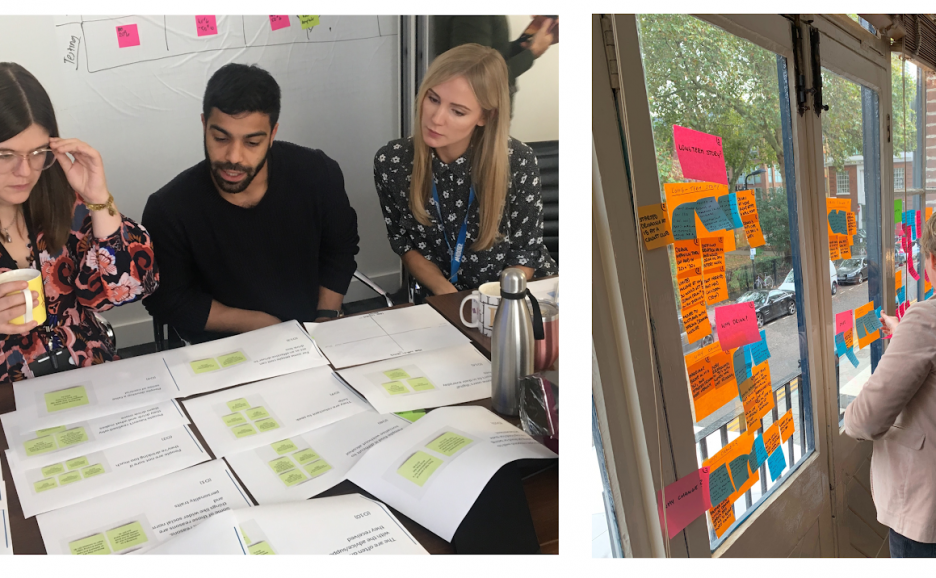

We also brought Drinkware along for the journey, coaching them on user-centred design and agile service delivery. They had opportunities to observe research sessions, participate in group co-analysis and get involved with ideation and prioritisation.

We showed Drinkaware how to complement quantitative segmentation with in-depth qualitative work. And how to collect, define and share user needs that real people would recognise as their own.

Some research takeaways

People can have a complex, lifelong relationship with alcohol. This journey can be filled with life-changing events, powerful emotions, small victories and many disappointments

People can start and continue drinking for many different reasons. Some of those are associated with wider cultural norms, others to do with personality traits or life events and influences. Drinking is easily available, widely accessible and the primary way to socialise. It’s deeply embedded in British culture.

People can drink more when they’re in particular situations or surrounded by certain people. For example, they might drink more than usual when their drinking companions are heavy drinkers. Some people don’t realise that they need to drink less, because they don’t think they’re drinking too much. And they find themselves being pressured to drink even when they’ve decided to cut down.

Their idea of what a “normal” drinking pattern is may shift depending on who they’re surrounded by or drinking with. For example, if they start a relationship with someone who drinks less they might realise that they’re drinking a lot more and start questioning if that’s ok?!

People also reward themselves with alcohol: for working hard, achieving something or even rewarding themselves for not drinking.

Over time, some people develop a ‘drinking routine’ that’s hard to break. Others’ drinking escalates quickly after a difficult event like divorce or losing a loved one; and often, they keep drinking the same way long afterwards.

Using standardised scoring tools and medical jargon is not helping people. They need a more personalised approach

Health care professionals and organisations like Drinkaware use an official scoring mechanism called the AUDIT-C to calculate the level of risk and provide advice accordingly. We also used this scoring as part of our screener for our research participants. And as with all research outputs, we found shortcomings with the AUDIT-C screening test. The results from these questions don’t represent people’s underlying behaviour, reasons for drinking and the challenges they’ve run into. People have a hard time estimating and so they interpret these questions in many different ways.

For example, someone scored themselves at ‘increasing risk’ when in real life they would be on the very extreme end of dependency. Having made some positive changes in recent months, this person had been struggling for years and even attempted suicide by mixing a large dose of alcohol and medication. She talked us through how she had been previously given unhelpful advice, repeatedly failed to make any meaningful progress and felt judged by those who were meant to help her.

People don’t recognise the different levels of dependency. There’s no middle ground for support

This theme around advice and help was persistent throughout our conversations. People are generally reluctant to seek help and struggle to find ways to reduce their drinking successfully in a sustainable way.

People don’t recognise the different levels of dependency. They think that support and seeking help is for “those alcoholics with the brown paper bag”. When in reality, they may already be “functioning alcoholics” or getting closer to more serious dependency.

Unfortunately, people don’t feel there is a solution for them within the support landscape; solutions seem too “extreme” for them. They may feel that support lines or chats are for “emergencies” not for them. The reality is, they might need external help to reach simple goals like not drinking Sunday to Thursday.

And that’s why by the time people decide to do something about their drinking, they’re relying solely on willpower and so struggling to make long-term changes. Sometimes leading to a yo-yo-like struggle between abstinence and really heavy drinking sessions.

Those who reach out often ended up receiving the wrong kind of advice and support. They may be referred to an AA support group where they feel thrown into the same pot as those who are in a far worse situation and are unable to connect with others in a meaningful way. When what they needed was to connect with someone similar to them.

But we also heard stories where support groups had a positive effect on people. A mom of two kids under 10 told us how she saw “the future me” at an AA meeting where another mom had been arrested the night before because she finished a bottle of wine, and decided to pop down to the shop for some more. Seemingly, a perfectly “functioning adult and a parent”.

The accidental power of personal reflection

Some people simply don’t know why they drink the way they drink and we uncovered this accidentally. At the end of the sessions, several people described how talking through their drinking in this way was extremely helpful. Having the opportunity for a safe space with neutral prompts to reflect on their lifetime of drinking was powerful. We had helped people be honest with themselves and with us.

Reflecting on the practice of design, ‘design accidents’ are often the most powerful opportunities. These are also known as design serendipity in the community. Digging further into this idea, we found theory from psychology that supports this finding. Officially, it’s called the Narrative Therapy Technique.

“I’ve found it really helpful for me, to talk through my drinking habits [..] it helped me make some sense of it all.”

This level of detail will give Drinkaware a new perspective on how to support people to reduce their drinking. They will be able to evolve their online products and offline services to provide more personalised solutions grounded in users’ needs.