Unmoderated testing for the UK’s new register of regulated professions

The register will help people understand what qualifications they need to work in a chosen regulated profession in the UK

Some professions, jobs and trades in the UK are ‘regulated’, which means you must have certain qualifications or experience to work in them.

We’ve been working with the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) to create a register of regulated professions. The service replaces the existing EU database and covers professional qualifications in everything from healthcare, education, and the legal profession.

The register will help people understand what qualifications they need to work in a chosen regulated profession in the different UK nations. And for overseas professionals, how their existing qualifications might be recognised.

One of our final steps in this project was to run an ‘unmoderated usability test’. This post describes what that is, why we did it, and how we did it.

Moderated vs unmoderated

You’ll probably be familiar with ‘moderated’ usability tests where we watch participants try to complete specific tasks using the service we’re building. In these tests we ask participants to ‘think aloud’ as they move through the service to help us better understand what they’re doing, thinking and feeling.

In a moderated test, the researcher is with the participant during the test. So we can ask questions, give more instructions, and intervene in the test to help move the participant between tasks, or get them back on track if they have a problem.

In an unmoderated test, we give the participant some instructions, and a time period in which to complete the tasks. But the participant completes the tasks alone.

And we use a variety of methods to collect the data we need to understand what they did and how the experience was for them. Things like performance analytics, questionnaires, and the information they enter into the service. We can also collect video recordings of the participant completing the tasks.

In unmoderated tests we can’t intervene when there’s a problem, or if the participant doesn’t understand the instructions. And if our data collection isn’t working properly, we won’t know until after the participants have completed the test. So this type of test needs more careful preparation, and a more complete and reliable service.

Here are a couple of articles if you’d like to know more:

- Remote Usability Tests: Moderated and Unmoderated – Nielsen Norman Group

- Using moderated usability testing – GOV.UK Service Manual

Why do an unmoderated test?

The Regulated Profession Register will allow people to check if a profession is regulated, find out what qualifications and experience are required, and contact the regulator to find out the process for becoming a recognised professional.

We don’t have a good way to run a private beta for the parts of the service for the general public. Mostly because it’s a new service, so there isn’t a pool of existing users we can invite to try the new version. And we can’t just make it public somewhere, because, well, that wouldn’t be a private beta.

So the internal assessment panel at BEIS asked us to find a way to show members of the public successfully using the service, outside of our moderated usability tests.

The panel wanted us to:

- demonstrate that external users can complete a live unprompted end-to-end journey

- (in a private beta phase) start collecting user data from the agreed methods

- show through performance analytics that users are successfully completing their journey and getting the information they need

- during private beta set appropriate benchmarks so the success of the service in public beta can be measured

We decided to meet this request by running an unmoderated usability test.

How we ran the unmoderated test

In some ways, preparing for an unmoderated test is the same as for a moderated test.

We need to:

- recruit relevant participants, decide what tasks we’ll ask them to do, and how we’ll ask the participants to do the tasks

- have a service that they can use

- decide how to collect data that we can analyse

- think through potential ethical issues and other research risks

But how we do each of those things is a little different for an unmoderated test.

For the unmoderated usability test, we created a research guide to think through and capture these steps.

Recruiting participants

Many market recruitment agencies have ‘panels’, large numbers of pre-screened potential participants, that they can recruit at relatively low cost. These panels are mainly used for large scale surveys, but they can be used for short usability tests.

We got quotes from 4 agencies. The best was quite good value, around £40 per participant, but it could not complete the recruitment within the time we needed. The one we chose was more expensive, but they could meet our timescale, and gave a higher incentive to the participants than the others.

Deciding tasks

The public part of the service is relatively simple. There’s a starting page, search pages for professions and regulators, and a page for each regulated profession and regulator.

We decided to ask the participants to:

- look for some professions they are interested in

- find out if the profession is regulated and how

- see what they might need to do to practice that profession

- complete the feedback form

A service to test

We decided to use the ‘production’ version of the service.

For some weeks, regulators have been using the service to add the information about their professions to the register. So, although they’re incomplete, the profession pages held the official information provided by regulators.

The participants would just look at information. They cannot change anything on the register, so there was no risk in giving them access to the production service.

Collecting data

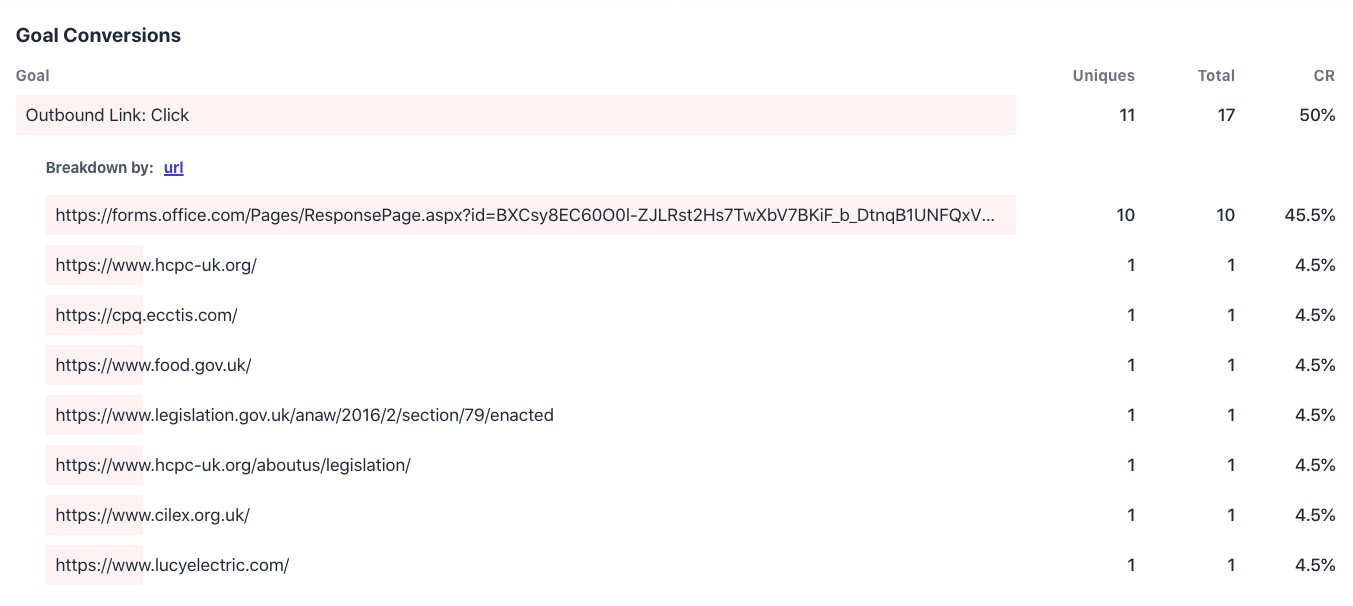

The service uses Plausible analytics which the team chose because it doesn’t use cookies. Many users will disable cookies, which makes getting accurate data more difficult. Plausible removes this barrier.

Before running the test, we thought about what we’d like to see in our analytics, and refined our implementation of Plausible.

In our Plausible dashboard we could see:

- how many profession and regulator searches the participants did

- which filters and keywords participants use in their searches

- which profession and regulators pages the participants look at

- which outward links to more information the participants click on

These are not possible with the analytics we currently have, but we would also like to have seen:

- how many professions or regulators the participants got in their search results

- how many profession or regulator searches participants do before they leave the search page or click on one of the results

The test also gave us the chance to try out our feedback form for the service.

Before running the test we refined the questions a little, and moved it to a Microsoft Form owned by BEIS.

The questions in the form were:

Overall, how did you feel about the service you used today?

- how could we improve this service?

- what did you come to the Regulated Professions Register to do?

- did you find what you were looking for?

- did you contact a regulatory authority directly after using this service?

- if you didn’t contact a regulatory authority, why not?

Knowing who completed the test

In an unmoderated test, we need some way to know which participants have completed the tasks so that:

- the recruiter can chase participants to complete and pay incentives to those who do

- we know how many participants we had in total when we create statistics

- we know how many participants to pay for

Recruiters will typically give each participant a unique ID, and we needed a way to capture it during the test.

For surveys, the panel recruiter may be able to pass the participant’s ID to the survey, and provide a link where we can directly record that the participant has completed the survey.

For this test, our feedback form has an optional question where a user can provide their email address. So we asked the participants to enter their ID there.

Potential risks

The participants were all completely anonymous, not providing any personal data, and not completing any potentially harmful tasks. So we could see no ethical concerns.

But the exercise had significant limitations in the number of participants and the completeness of the register.

There was a risk that restricting the test to just 10 participants would not give us enough data to produce meaningful findings.

And at the time we ran the test, the register was only about 25% complete. So there was also a risk that participants would not be able to find information about any relevant professions.

Creating findings

For larger unmoderated tests, we are often looking to create statistical findings. For example, n% of the participants chose option x, or n of m participants had to fix errors when they did y.

For a test with 10 participants we couldn’t produce statistical findings, but we could look at their activity in Plausible, and review their responses to the feedback survey.

What we learned from the unmoderated test

Despite the limitations, we did get meaningful findings from the test:

- participants found and used all parts of the service

- more than half the participants used mobile or tablet (despite the recruiter suggesting that they use ‘a computer’)

- participants successfully used the keyword, sectors and nations filters (although the regulation types filter was not helpful)

- participants using assistive technologies such as screen readers, voice control and head controlled keyboards completed the tasks

- reported satisfaction was reasonable

- the completed professions pages provided good information (although some have too much technical detail)

We also tightened up our analytics, and identified some ways to improve them further in future.